This article originally appeared in the October 1996 issue of OUT.

"Hairdressers, interior decorators, figure skaters, Catholic priests," says Allan Berube. "Church organists. Travel agents." He grins roguishly, eyes crinkling as he ticks off the list. "Waiters and virtually all men other than ministers working in the wedding industry."

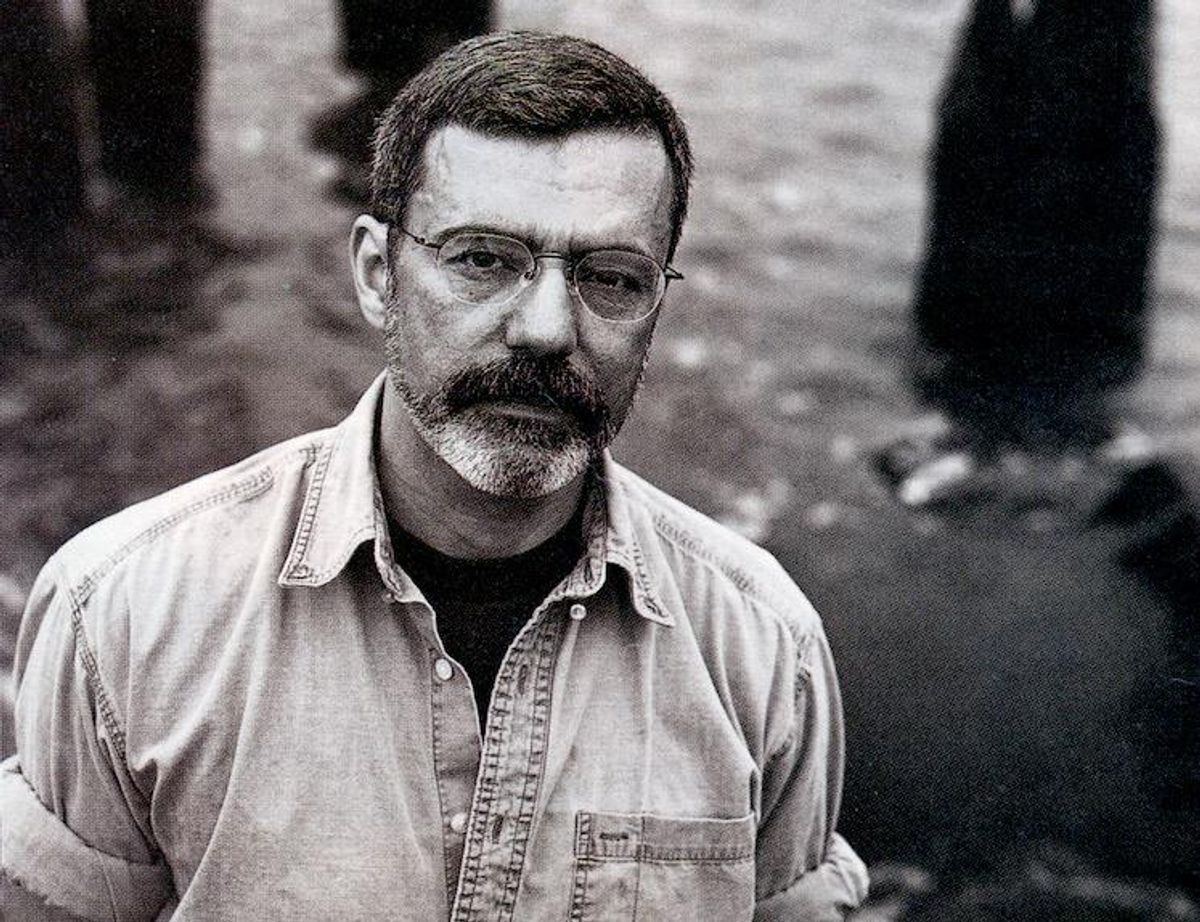

Allan Berube is talking about the people who do what he calls "queer work," the subjects of his research for more than five years, which won him a prestigious $300,000 MacArthur "genius grant" in June. Past winners have included gay dancer and choreographer Bill T. Jones and lesbian poet Adrienne Rich but never anyone working in the field of lesbian and gay studies. At 49, an independent labor historian without a university degree of affiliation, Berube is being honored for a career of studying gay and lesbian social history and lives on the job.

At the offices of Service Employees International Union Local 250 in Oakland, California, during a recent meeting of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender labor activists, Berube is sharing his historical research with an enthusiastic, informal group of blue- and pink-collar workers. A slim, neat man with a salt-and-pepper beard and a black leather jacket, he smiles engagingly at the men and women crowded into a small room. "Costume designers, ballet dancers, personal secretaries, travel agents," he reflects. "I think I've dated most of these men at one time or another. What are some of the stereotypes of queer work you've heard of or done?"

Most jobs, explains Berube, have historically been divided into men's or women's work, pigeonholed and white or "colored" work, even seen at different times as especially well suited for Chinese or Korean or Irish workers. Berube talks, similarly, about the "homosexualizing" of jobs such as gym teacher, nun, UPS driver, and carpenter for women, or nurse, figure skater, and fashion designer for men. At its worst, he says this kind of queer work can be a "stigmatized ghetto, a trap--all we're good for."

But Berube maintains a kind of amused affection for the stereotypes. "Many middle-class gays try to distance themselves from the fag hairdresser or lesbian truck driver," he says, "but people have always used those jobs to transform a trap into a refuge." And, argues Berube, the stereotypes are an excellent way to understand labor history, and the place of queer lives in that history. "There's this myth," he says, "that gays aren't working-class, and that labor unions aren't queer. But if you look at the jobs considered to be queer work, you see how decades before the middle-class gay movement, people used their unions to improve their lives as queers."

Allan Berube is an intellectual who has chosen his own path. Growing up working-class in Massachusetts and New Jersey, Berube recalls, "I always wanted to figure things out. I loved ideas. So school was going to be the way I escapes. But once I got to college I felt disoriented and torn apart." Berube dropped out of the University of Chicago in the turbulent spring of 1968: "I was taking a multiple-choice test on Swinburne, and the city was under martial law. I just walked out and never went back." He moved to "a gay hippie commune" in the Haight-Ashbury and followed his own path through queer work as a nurse's aide, temporary typists, receptionist, and waiter.

His interest in history led Berube to co-found the community-based San Francisco Lesbian and Gay History Project, and he continued to dig through old archives, newspaper, files, and records in search of previously undocumented queer lives. After the accidental discovery of a gay service member's letters in 1979, Berube spent years working part-time to support his research as he crisscrossed the country finding and interviewing gay and lesbian veterans. Berube presented his work in progress in slide shows at community centers, veterans' posts, and conferences. His book Coming Out Under Fire, a pioneering study of lesbians and gay men in the military during World War II, was published to critical acclaim in 1990; with filmmaker Arthur Dong, he turned it into an award-winning documentary film.

Oral histories of several veterans led in turn to Berube's research on the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union, a militant and heavily gay male union of freighter and ocean-liner crewmen active from the Depression to the early '50s. In its heyday, the union was "a third red, a third black, and a third queer," according to one seaman interviewed by Berube. Its members called themselves "queens" with names like Grace Line Gertie, Madame Queen, and Miss Leprosy; they dished the passengers, stood up for each other against straight management, and demanded respect as well as better pay. Berube recounts with relish the story of the time a crewman called union member Jay Shannon a "fruit:" "Mother Shannon grabs a big soup ladle and boy, she slaps him right across the head. 'Now,' she says, 'you son of a bitch, I bet I'm the meanest fucking fruit you ever saw,' and I mean, she drew blood. That's the way Jay Shannon would do it, so you didn't fuck with the Marine Cooks and Stewards."

Berube likes to draw a lesson from his research on the ships. "You begin to see," he says hopefully," how people so long ago were able to break down the walls of mistrust. There's a history of alliances rather than identities."

Berube own alliance-building has mostly centered on community institutions, activists, and labor unions; he remains, "in terms of class and credentials," an outsider in the academic world of gay and lesbian studies. "I've never patched together an intellectual community with other activists and with freelance scholars," he says with a shrug. "But we're not in the footnotes, not invited onto panels, and we get dismissed as not theoretical enough." The MacArthur, he says, is significant precisely because, as the first grant ever in the field of lesbian and gay studies, it honors an independent, community-based historian. "What was interesting to us about Allan," says Catharine R. Stimpson, director of the Fellows Program for the MacArthur Foundation, "was not only the quality of his work but the fact that he worked outside of establishe dinstitutions and came up with innovative ways to do history. He has exceptional creativity."

Berube, who says he's "excited" by some new gay and lesbian scholarship, nonetheless is concerned about the field's insularity. "At its worst," he complains, "it's so abstract, text-based, career-oriented, concerned with developing an insider jargon that it just doesn't hold my attention." He looks up earnestly, running a hand through his cropped hair. "Scholarly work, for me, always has to answer the questions: Who's in the conversation? What is it used for? Who does it make more powerful?"

At the Oakland labor conference, it's clear who Berube means his work for. The crowd is devoid of buff gay clones and high-fashion lipstick lesbians; neither are there idealized porn fantasies of working-class hunks. Instead, under the heating ducts and fluorescent lights, overweight women in slacks and middle-aged men in shirtsleeves--regular people--sit in folding chairs talking about striked and shutouts and scabs. In the postmodern, cynical, and for-sake world of urban gay culture, their sentiments would seem corny--almost exasperatingly out of date.

A straight, white-haired Irish union president brings greetings to the "brothers and sisters," and calls them "to fight for liberation." Dolores Huerta, the fiery United Farm Workers leader, recalls the early 1970s when, as a straight Catholic mother of 11, she picketed for gay rights. "Down with racism!" she finishes, waving her tiny fist in the air. "Down with homophobia! Down with California table grapes!"

Berube, sitting under a dingy poster proclaiming 'An Injury to ONe is an Injury to All,' looks more attentive when Mary Kay Henry, the young lesbian director of the health-care division of SEIU, steps forward.

In contrast to the previous speaker, who has been extolling "the glory of the powers of resistance," Henry is blunt. "I don't want to put down the spirit we have," she says, "but we can't change things unless we get off our butts. Workers have very little power in this country."

The speeches wind down, and Berube stands up to kiss the legendary gay organizer Harry Hay, now 84, and Hay's boyfriend, John Burnside. The lofty slogans about solidarity and struggle give way to genuine, unaffected friendliness as other unionists come up to offer Berube congratulations on his MacArthur. "Now you can pay your rent!" cheers one woman. A carpenter chimes in, "These days every day's a new adventure. You don't know if you'll have a job or not. It's great you can count on this."

Berube beams as he tells friends he plans to use the MacArthur to finish his book on the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union, Shipping Out. For now, his life is split between New York and San Francisco; Berube says he's happiest in places where people are not defined solely by their gayness. "Too many people assume queer life takes place off the job," he says, "in bars and bedrooms. But there's more. This is the world, and we live in it."