The streets felt especially silent in Levittown at 8 p.m. on September 20, just hours after Hurricane Maria had ripped through at wind speeds up to 155 miles per hour. One of the worst storms in Puerto Rico's history, the storm shredded trees, tore off roofs, and hurled projectiles around the home of Jaime Luis Santana-Rivera's mother--but they'd survived.

Santana-Rivera took shelter there, in that municipality of Toa Baja, rather than at home in Carolina, an area known to be more susceptible to flooding. After a long bout of vigilance during the storm, he'd gone to sleep, but woke up briefly hoping to return worried messages from his partner, Abdier Benitez, in New York. In search of a better signal, Santana-Rivera went outdoors, along with Nero, a dog the couple shares in tow.

That's when he noticed the water rising.

"I'm like, it's not raining," he recalls. "Why is the street wet, and an hour ago it was dry?"

No cell reception. Cars rushed away in the opposite direction. The water was creeping up to the doors of his vehicle.

"I woke up my mom, and I told her we may have a problem," he says. "She thought it was [water clogged by blocked sewers]. I'm like, No, sweetie, that's not what's going on. Everything is flooded; we need to get out of here. We took the dog, we took the cat; my mom was still trying to put all the clothes and the furniture and everything up so it [wouldn't] get wet. I'm like, Forget about that, we need to get out of here. Forget about everything."

Scrambling to reach higher ground, they found police and military officials prepared to take them to an official shelter. He'd just waded through waist-high water with his mother, Haydee Rivera, and his aunt; in all the frenzy, Santana-Rivera says, his cat nearly drowned when he fumbled, almost dropping the carrier. He'd left so frantically and suddenly that he forgot to put on shoes.

Related | Trans Power & Queer Visibility at Puerto Rican Pride

But he had to go back. The family of his partner lived close by--what if they were sleeping? No alarms had sounded to warn residents of the area, Santana-Rivera says. His mother was furious.

"She was like, You're going where? Are you nuts? I'm like, I'm sorry, I can't leave them there," he says. "I just found out what was going on because I woke up; I was sleeping. What if they don't know what's going on? And they drown? I have to, I have to."

He left his mom, safe with the officials. The water had risen so high that walking was impossible; he literally swam the entire route to his boyfriend's family. Santana-Rivera arrived screaming.

They'd taken shelter on the second floor of a neighbor's home. Fearing a dangerous swim back, he stayed the night.

After the flooding recessed, the damage surfaced: The family of Santana-Rivera's partner had lost everything.

"[My boyfriend's mother] began crying; that's what's really painful for me," he says. "She didn't cry because they don't have a car or furniture, she began crying when she saw she had a closet full of pictures of her son, my boyfriend, and his two brothers. When she saw that all the pictures were ruined, she started crying. I was like, Oh my god. What can you say? I was like, You know what? They are alive, and so are you. You need to be grateful for that, so forget about everything else."

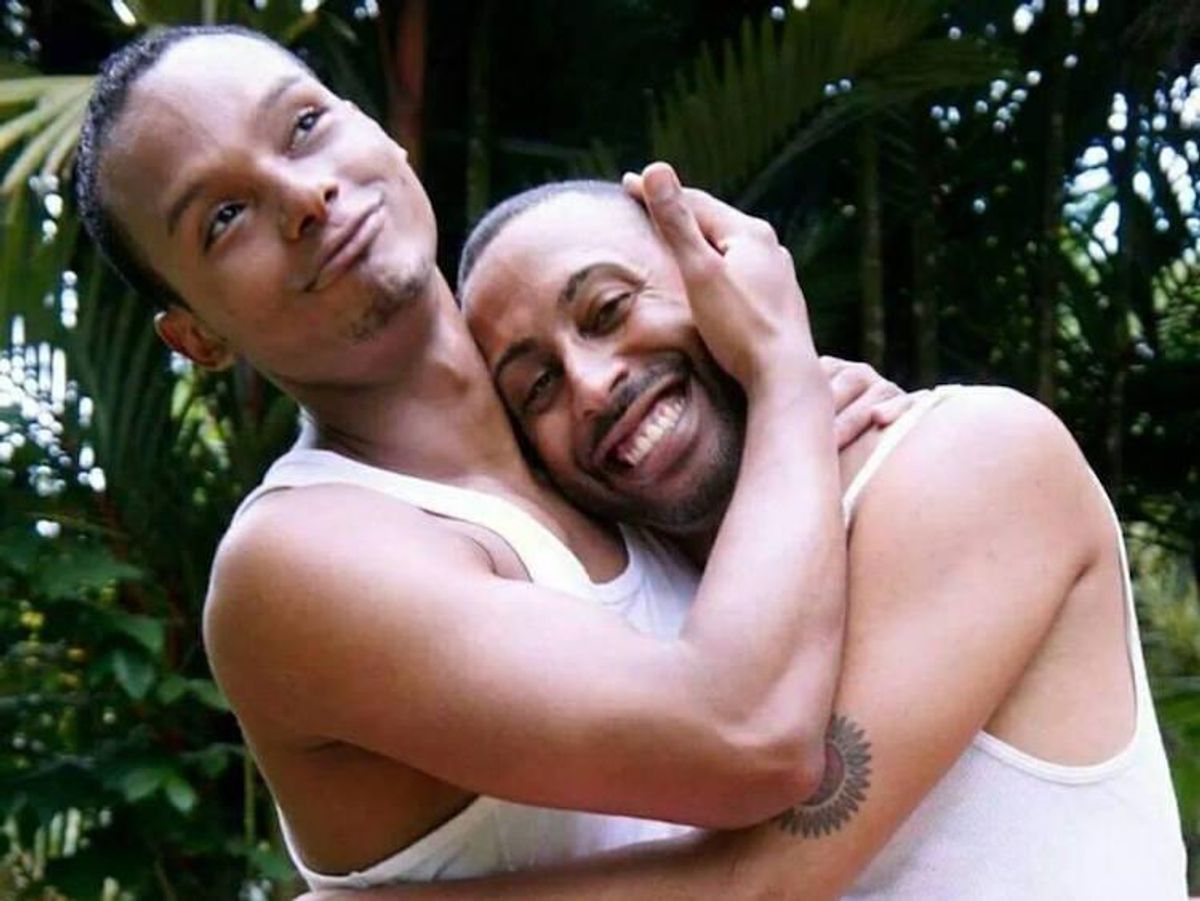

(From Left): Santana-Rivera, Abdier's mother, Abdier's brother, Dog Nero

Despite the water level drop, there was still more flooding on the way back to his mother's home. He swam, again, searching until he located her at his grandmother's home. His family wasn't too happy with him at first, but later understood. Benetiz, who's been Santana-Rivera's partner since 2011, would have done the same for him, he says.

"The thing I cannot believe is how this tragedy, because it is a tragedy, has made the family of my boyfriend and my mom to come together," he says. "[Before], they were like, Yeah, hi, how are you doing? But now it's just the opposite. This can bring people together--if they decide to. It didn't happen for the best, it just happened. You have to decide whether you're going to take it as a lesson or not."

Santana-Rivera's mother didn't suffer any damages to her home, and his own place in Carolina is fine, too. They are grateful, of course, to be safe. At least 36 people have died as a result of Maria, whether directly during the storm or after for lack of medical treatments requiring electricity. Some experts believe the count to be significantly higher, and that it will likely continue to climb, as power has yet to be restored, many hospitals are without generators, less than half the island has water, and supplies outside the metro area are increasingly scarce.

Related | Puerto Rico Death Toll Rises to 34 After Trump Downplays Hurricane Devastation

A storm of this scale carries complex, long-term repercussions. The power outage caused by Hurricane Irma, only weeks before Maria, left many Puerto Ricans without work. Now, even more are unable to generate any income. While FEMA is offering some monetary aid, the forms must be filled out online--and finding wifi on an island without electricity isn't easy. Regardless of the potential $500 in help, that's not enough money to carry anyone for an extended period of time. And this stretch without work will be a lengthy one.

Santana-Rivera is a contract employee for the Department of Health working on a HIV/AIDS surveillance project. Because of the storms, he has hardly been able to work at all throughout September.

"I'm not the only one," he says. "Everybody's in the same boat, and we need resources. We need people not only to be worried about what happened before the hurricane... what happens if I don't have my paycheck at the end of the month? How am I going to survive that? That's also part of the tragedy."

There are ways to help, like donating to the Maria Fund. You can also support efforts that cater specifically to the LGBTQIA community, like this fundraiser that will put money directly in the hands of people who need it. It's headed up by a Puerto Rican in the diaspora in collaboration with the Puerto Rico Trans Youth Coalition. Another project aims to facilitate relocation in Philadelphia for LGBTQIA evacuees in need of assistance. San Juan's Centro Comunitario LGBTT de Puerto Rico is also raising funds to provide relief: Batteries, flashlights, food, and a generator to power the center.

Related | Here's How You Can Support Puerto Rico's LGBTQ Community Center

Because of the tightened financial strain for those on the island, Puerto Rico's LGBTQIA organizations will likely see a drop in fundraising. Santana-Rivera, who also works for the Colectivo Orgullo Arcoiris, the year-round nonprofit that heads up San Juan's Pride festival, wanted to arrange a fundraising event, but without electricity, and considering the employment situation, that seems impractical, if not impossible. Help from outside--to keep existing services going, and to meet an increase in need--will be crucial.

"I don't know when we're going to electricity again," Santana-Rivera stresses. "Maybe it's not four months, it's five. Well, we survive. That's the important part. But once again, it's not only surviving the hurricane, it's surviving what happens after."