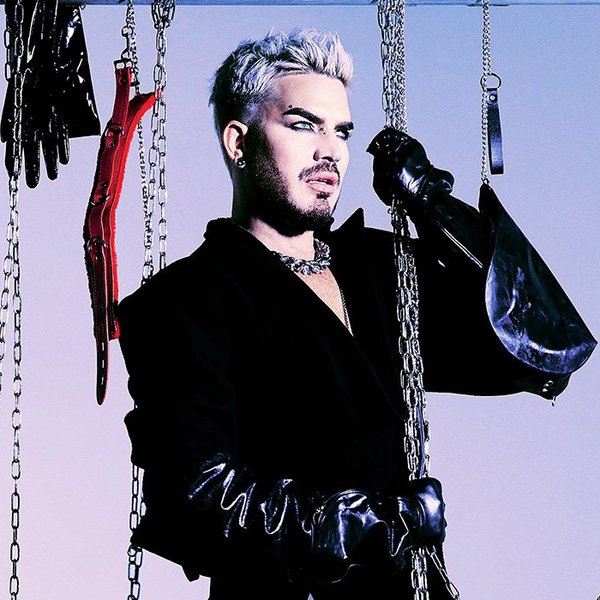

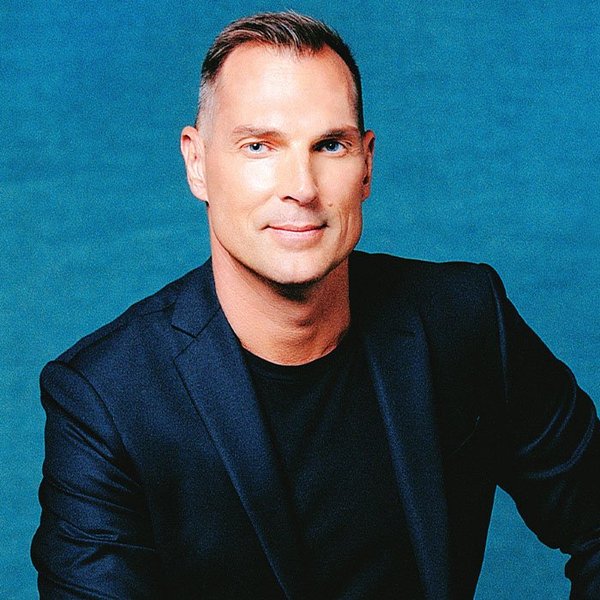

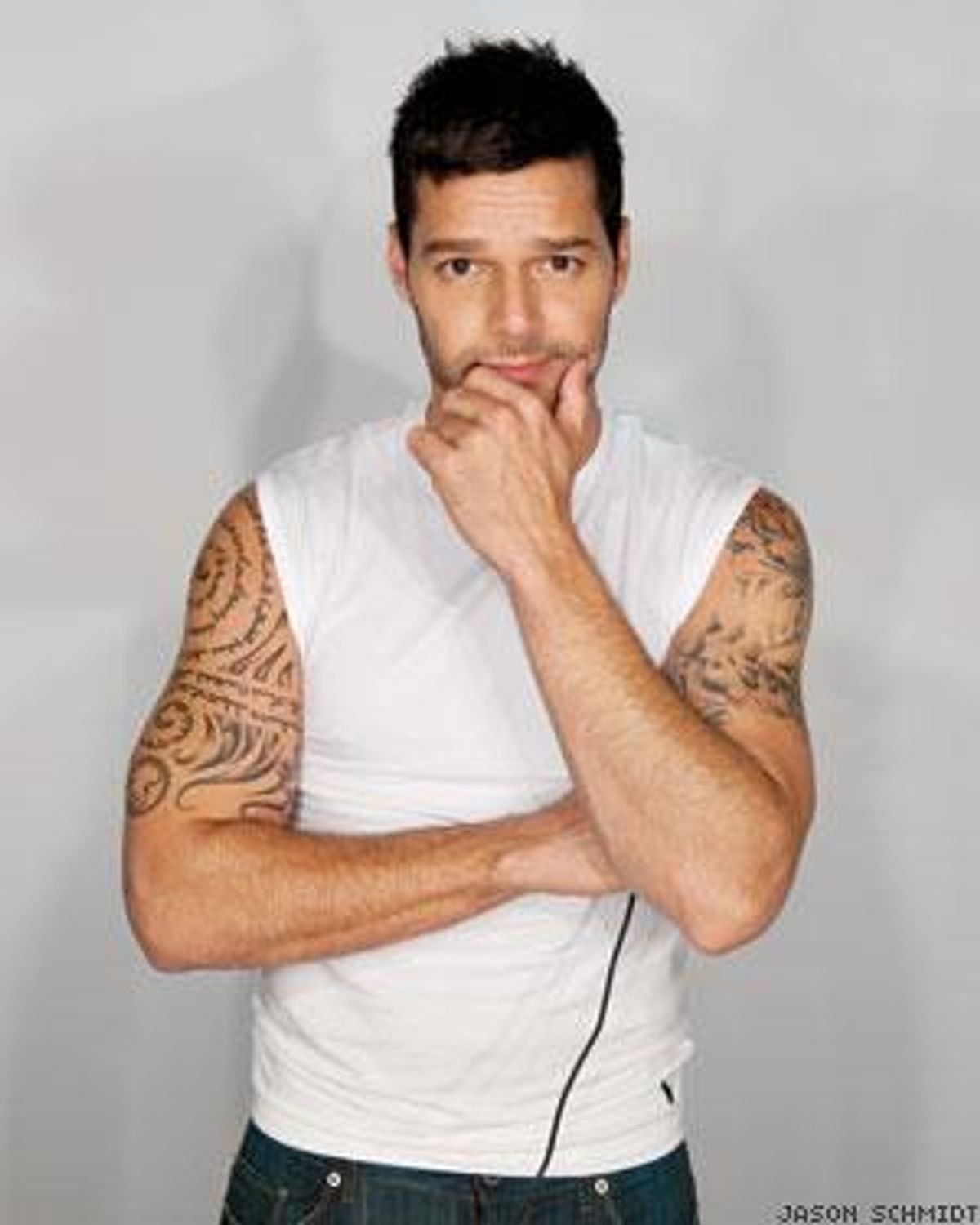

On March 29th of this year, Ricky Martin made a decision that would change everything. He posted a letter on his website and linked to it from Twitter. The letter outlined the process of writing his upcoming memoir, during which Martin came to realize that he needed to free himself of a particular burden. Writing about it, he added, was 'a solid step toward my inner peace and vital part of my evolution.' He closed the letter, with a beautiful, eloquent, and simple declaration: 'I am proud to say that I am a fortunate homosexual man. I am very blessed to be who I am.'

It is a warm October afternoon in Miami Beach, and the fortunate homosexual man is tearing up. We've just started talking, but Martin can barely contain his elation. It is sweet and touching and genuine. When I suggest that few of his fans could have imagined in January that he would be on the cover of this year's Out100, he has to steady himself, sucking in the air and releasing it in a low, long exhalation. The hum of jet skis and motorboats on Biscayne Bay fills the silence. A breeze shifts the long, white drapes that separate the living room from Martin's waterfront garden. 'I get emotional,' he says, finally, fanning the air gently with his hand. 'What a beautiful way to start.'

He's right. There is something beautiful in witnessing a major celebrity in the throes of profound and real transformation. A week before we meet, Martin had made a surprise appearance at the annual Human Rights Campaign national dinner to pledge his support. 'Something as simple as standing at that dinner and saying, 'I'm gay,' creates so may emotions I've never felt before,' he admits. 'I didn't do it earlier because of fear, and, bottom line, it was all in my head. I was seduced by fear, and I was sabotaging most of my life -- my music, my relationships with my friends, with my family, with everybody. That's something I need to share because I know that a lot of people are going through what I went through, no matter what their age, and fear cannot control us.'

Martin is about to share big time -- with his new memoir, Me, a remarkably heartfelt account of his journey from teen group Menudo to fatherhood, delivered in a frank, conversational style that doesn't economize on the truth. It includes accounts of his first passionate affairs -- with men and with women -- as well as his struggle to reconcile his conflicted yearnings with his rapid ascent in America. The pivotal year is 1999, at which Martin performed his World Cup anthem, 'La Copa de la Vida,' at the Grammys. Largely unknown in the United States beyond Hispanic audiences, he left the stage as a breathless Rosie O'Donnell (the evening's host) exclaimed, 'Who was that cutie patootie?' Between that quip and the well-intended advice of Madonna to 'stop doing interviews -- everyone knows who you are' were a few short hops separated by 17 million album sales for his first English-language album, Ricky Martin, covers on Time and People, and a 25-date U.S. tour that sold out in eight minutes.

Contrary to Madonna's comment, it's arguable whether Martin even knew himself. In Me, he presents much of his life as a subconscious effort to avoid confronting unpalatable truths. It's one explanation for his nonstop work ethic. He was always, he says, a performer who didn't know how to say no -- 'perhaps because if I stopped I would start to think.' A growing interest in India -- a giant Buddha stares passively from his hallway -- would eventually help him resolve those tensions and lead to the introspection that animates his memoir. 'In this book, I am sharing the moments that triggered intensity, like passion and love, and that brought me to a place of understanding or a place where I really started asking a lot of questions, connecting the dots,' he says.

It was connecting the dots that led directly to Martin's tweet last March. In his memoir, he recounts how friends and colleagues remonstrated with him to hold off: 'I ignored all their recommendations, and by the end, when they came to me with the argument that I shouldn't do it during Easter because it might offend my Christian fans, I said: 'What part of 'I can't take it any more' do you not understand? What about me?''

Two people who didn't intervene to stop Martin were his parents. 'My father is an amazing human being,' says Martin. 'He was the first one to tell me, 'Come on, share your love.' ' As for his mother, she flew to Miami for a visit the same day he published his letter. Martin held off posting it until he knew she was safely in the air, beyond the reach of gossipy chatter, and made her read it the moment she arrived at his house. 'As soon as she finished,' he writes, 'she stood up, gave me a great big hug, and started to cry like a baby.'

M artin is not the first pop star to come out -- a string of musicians got there before him, but while many enjoyed significant fame none has achieved such stratospheric heights of idoldom. And none had to contend with the dual responsibilities of being gay and a crossover Latin music star -- or a 'symbol of the new status Latin culture holds in mainstream America,' as The New York Times dubbed him in 1999. That seems like an awful lot of symbolism for one man's shoulders. Martin shrugs. 'I am a minority twice,' he says. 'I am Hispanic, and I am a gay man, and they both struggle. Is it a big responsibility? It can be as big as I want it to be, and I believe there's a lot still to come.'

Martin doesn't skate over the oppressiveness of Latin machismo that made his coming-out such a milestone back home, one not always appreciated by the press and bloggers in the West who treated it as no big deal. At the same time, he insists that his own 'Latin lover' vibe was always genuine. 'A lot of people go, 'Wait a minute, so 'She Bangs' became a 'He Bangs?' ' -- he laughs -- 'No, I never lied. That was my truth at that moment. And when you are on stage you just are. Mind you, as an entertainer if you make a move and you get a reaction, trust me, you are going to make that move again -- that's what we entertainers live off. Do I think it's going to be the same now? I don't know, and,' -- his voice drops to an urgent whisper again -- 'it doesn't matter. It feels so good that it can't be wrong.'

Not content to represent two minorities when he could represent three, Martin became a single parent just over two years ago after identifying a surrogate mother on the Internet. He thinks now that he was dealing with a lot of residual guilt for having abandoned his younger brothers when he joined the gilded cage that was Menudo, but he was also inspired by his work with his children's foundation, launched to help disabled children in Puerto Rico and later broadened to combat child trafficking and prostitution. In Me, he robustly rejects criticism of his choice to raise his twin boys, Matteo and Valentino, alone, with some familiar arguments -- many great people are the products of single parents -- and some less so. All families are different, he says, before adding, with a priceless flourish, 'being unique is fabulous.'

As it happens, his two boys do have another man in their life, one who does not materialize in Me, but who has recently become a major part of Martin's world. 'I am in a relationship, and I am in love, and it's incredible that I'm actually talking about it,' he says, adding that it's not in the book because it was too soon to write about it. 'It was a moment to nurture a relationship, not a moment to talk about it. And I was living one day at a time in this relationship because I was a father first and foremost -- I wasn't looking for anyone.' Martin won't reveal much more, except to say that his partner is also from Puerto Rico and loves his children and is loved by them in turn.

In the end, of course, everything is connected (back to those dots again) and Martin credits his boys for lighting the fuse that led him to come out. The turning point was that chapter about fatherhood. As he pondered why he'd wanted children, he cycled back through a chain of linked events and consequences. 'Why did I decide to be a father? Because of my work with my foundation. Why my work with my foundation? Because of my trips to India. Why did I want to go to India? Because I wanted to detach from fame, because I wanted to look for silence. Why? Because I didn't like interviews, I didn't like being famous. Why was that? Because maybe I was being invaded by questions about my sexuality. Hmmm. Why did I feel invaded?'

Above all, he says he worried about Matteo and Valentino having to answer for their father's untruths. How would they respond as they grew older? Would they have to lie on his behalf? 'How could I teach my kids to lie?' he asks. 'How could I teach them not to be themselves?' And, as simple as that, he realized he couldn't and wouldn't. 'My children will grow up with no prejudice,' he says. 'As parents, we need to create a new way of thinking for our kids, in which we accept, and we love, and we can vibe with everybody.'

On cue, it seems, the boys awake from their afternoon nap and are brought downstairs to daddy. Martin has a small retinue of loyal and longtime staff, more like family, and they start clucking and fussing over the kids, amusing them with clown faces as they run around the lawn grabbing at flowers to present to the adults, tokens of their affection. Martin laughs as they stumble in their haste and launches into a proud-father monologue, detailing their quirks and foibles: how Valentino insists on eating with his hands, covering his face with pasta; how he jokes that Matteo is 'half Puerto Rican and half Chinese' because of his overweening fondness for rice. And he frets about separation issues when he returns to Broadway in 2012 to play Che in the revival of Evita, his first stage role since he played Marius in Les Mis'rables in 1995, before reassuring himself that other Broadway parents deal with much the same.

And there is, of course, his new partner. Martin imagines a day when he'll be walking down a red carpet with his man and his boys, right behind Neil Patrick Harris and David Burtka and their twin kids. 'How awesome will that be?' he asks. Well, very.

See all of our 2010 Out 100 honorees here.