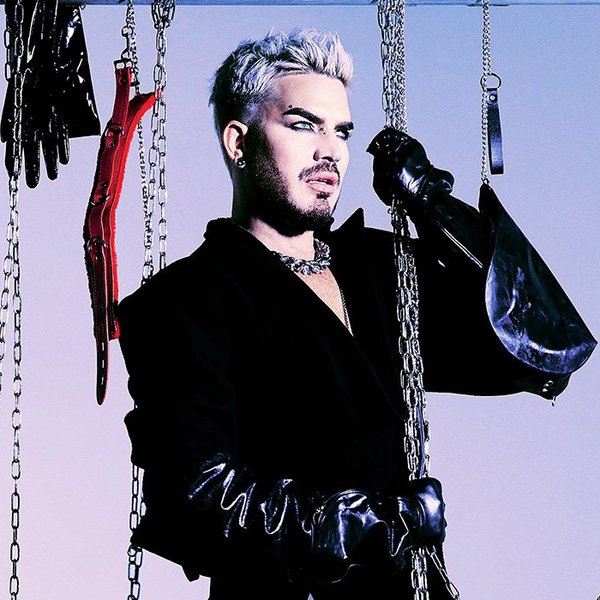

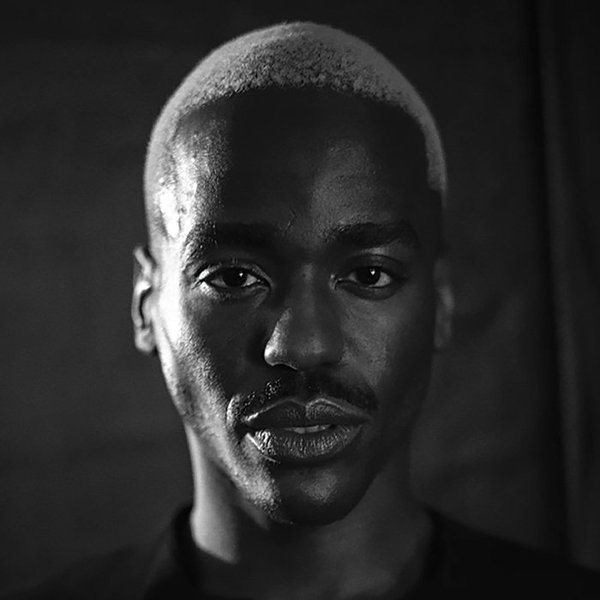

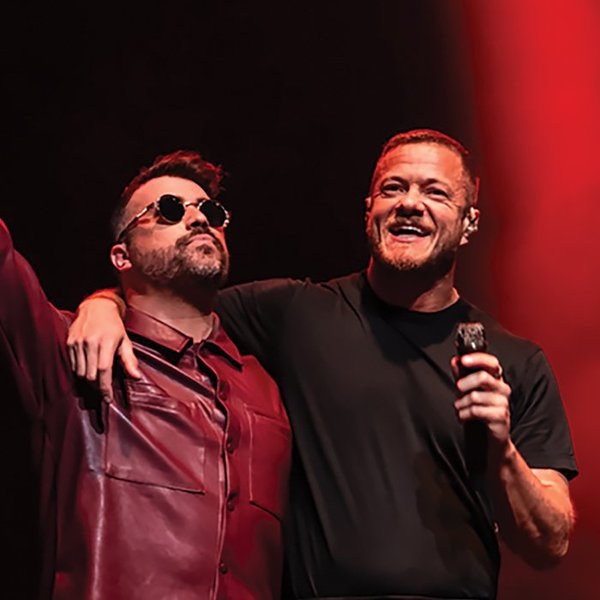

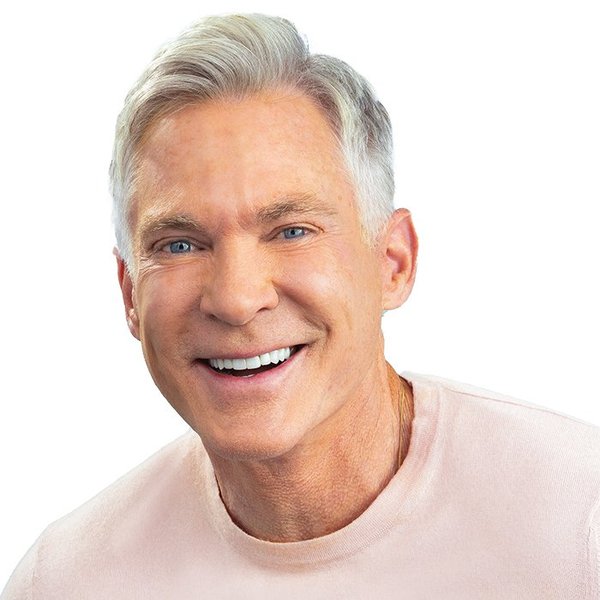

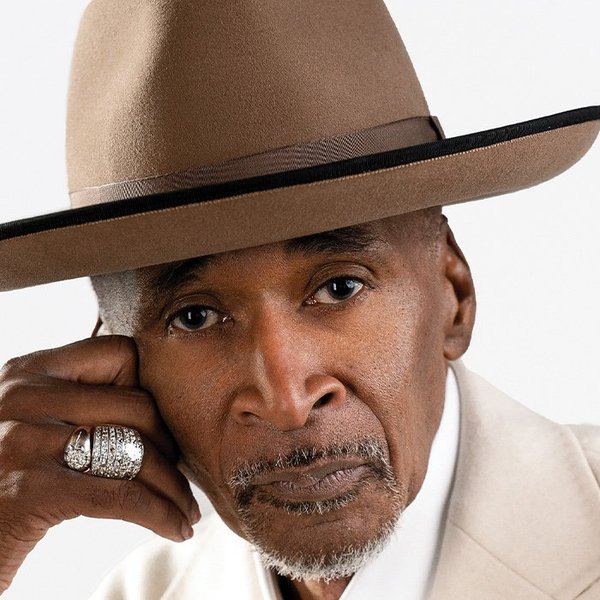

Photography by Danielle Levitt

Studying the history of slavery for his movie The Butler, Daniels was struck time and again by a simple observation: "The slaves who were laughing on the boats from Africa were the only ones who survived; those on the plantations laughing and singing were the ones who survived." The director, lolling against a pile of cushions on his bed, throws a glance to see if his words have landed. "That's how we made this movie -- by bringing laughter into ordinary places, because that's how we see life." More particularly, it's how Daniels sees life. In Lee Daniels' The Butler, as in his earlier movie Precious, scenes of the most abject suffering are interspersed with moments of levity and camp that puncture the tension.

Whether you feel comfortable laughing during a movie that documents the lives of the marginalized may depend on where you stand. "When I first tested Precious, it was at the Magic Johnson Theater in Harlem, for an all-black audience, and it played like a comedy," Daniels says. "And when I played it for a white audience in Sundance, you could hear a pin drop."

That Daniels has found a cinematic language that speaks to black and white audiences is part of what makes him -- a black, gay director -- unique. As a child growing up in Philadelphia, he experienced both worlds, first as a beat-upon gay kid in an impoverished black neighborhood, then as a beat-upon black kid in a privileged white neighborhood. "I learned to train my bowel movements, my piss, so that I wouldn't have to go to the bathroom all through school," he recalls. "And then I'd run home."

Although he plays it down, Daniels's childhood was fogged by the kind of family dysfunction and struggle that animates his movies. He remembers his father -- a cop who was killed during a raid on a Philly bar when Daniels was 15 -- dumping him in a trash can after catching him in his mother's red pumps. "When I came out it was because I loathed my dad so much -- I couldn't understand how you could, with an extension cord, beat a 45-pound kid just because he's aware of his femininity," he says. "For me it really created a world where I understood Precious, where you learn the power of the imagination. And that's how it began for me."

The narrative of Daniels's hard-living, hard-working life is a movie in itself, and maybe one day he'll make it. He watched lovers die of AIDS in his arms ("I was HIV-negative when everyone around me was dying -- I should be dead"), hit rock bottom on crystal meth, and came by his two adopted kids in an unlikely way: after his brother was jailed. "He called and said, 'I'm going to be there for a long time; I got this girl pregnant, she doesn't want the kids, and I have a feeling she's going to abandon them.' " No wonder he doesn't feel comfortable in the slick, oily culture of Los Angeles. "In L.A. they make you feel insecure, like you're always looking at the stars and you feel like you're not one of them," he says. "You feel like, 'I'm nothing.' It was what my father told me I was, and I knew I had to get out of there."

But the man who has already won Oscars for his movies Monster's Ball (which he produced) and Precious is aware that his insecurities are an inseparable part of his talent. "It's always when things are really good for me that I feel I'm not worthy of it," he says. "When Halle [Berry] won her Oscar [for Monster's Ball], I remember her calling, saying, 'Are you going to the Vanity Fair party?' and I'm strung out in the Chateau Marmont, methed out of my mind, thinking I didn't deserve it." He pauses.

"I have to be really aware of it, and always talking about it -- and be truthful about it to the point of ugliness so that it keeps my ass in check."

Photographed at the Campbell Apartment in New York City on September 19, 2013

SLIDESHOW: See the Complete Out100 List