This article is the first entry in Out's package of 50 ideas for the future of the LGBTQ+ movement. The rest of this package will be published on Out throughout Pride month.

Just two days before the 2016 presidential election, Zoe Leonard read her iconic poem, "I want a president," at New York City's High Line Park, documented for posterity on YouTube. She's perfectly framed by three patriotic buntings behind her, wearing a brown leather jacket and a bulky burgundy scarf, with her hair styled in that close-cropped, curly on top, distinctly queer kind of way.

"I want a dyke for president," reads the artist and activist, her tone measured and steady. "I want a person with AIDS for president and I want a fag for vice president and I want someone with no health insurance and I want..."

The poem, inspired by poet Eileen Myles' 1992 write-in presidential campaign as an "openly female" candidate, invites the reader to imagine a world where the most powerless people in the nation are permitted to ascend its most powerful seat. Reading the poem at the High Line more than 20 years after writing it, Leonard notes that she no longer thinks that way about identity politics, that she no longer believes that a person's identity tells you anything about their political leanings. Still, the question she asked in the poem remained an intriguing one to ponder on the eve of Hillary Clinton's defeat. Had the former Secretary of State beaten eventual president Donald Trump, she would have become the first female president in United States history. For many voters, her win would have represented an empowering feminist victory for all womankind, while others saw her whiteness, her wealth, and her hawkish, at times anti-Black political background as simply more of the neoliberal same.

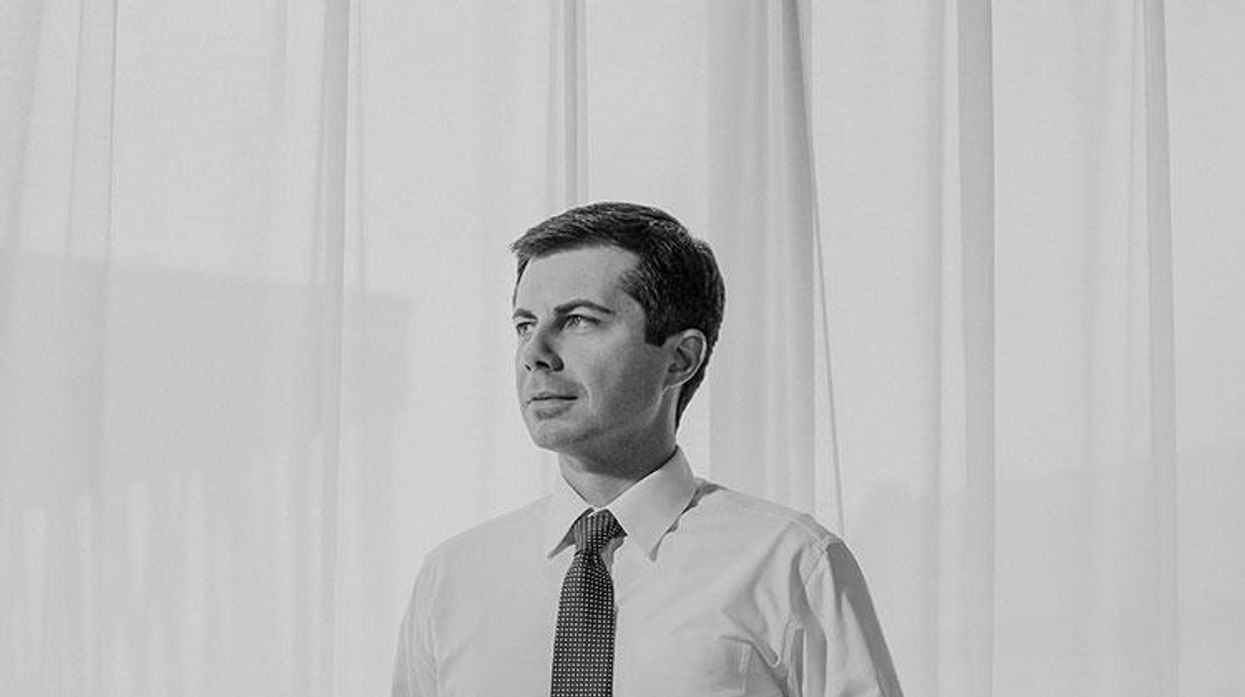

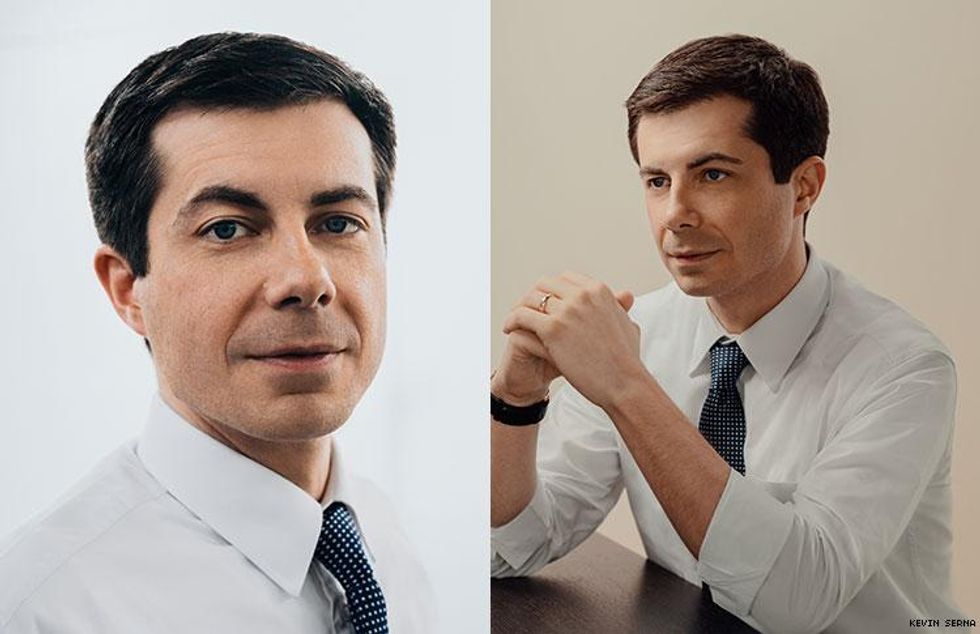

The question Leonard asked remains no less relevant today, as the 2020 election boasts the most diverse field of presidential candidates ever, all vying for the Democratic nomination. Six of them are women, six are people of color -- one of them is even gay, though he's nothing like the deviants and untouchables found in Leonard's poem. Pete Buttigieg is not a dyke, he hasn't lost a lover to AIDS, he has probably never wanted for air conditioning in his life, and his teeth look great -- on camera and in person. He's a 37-year-old Harvard grad, a Rhodes Scholar, a child of academics, and an Afghanistan War veteran. In contrast with the political outsiders that Leonard describes in "I want a president," Buttigieg is a career politician whose resume stretches back to a post-grad consulting gig on John Kerry's 2004 presidential campaign. He is now in his second term as the mayor of South Bend, Indiana, a position he has held since 2012.

Buttigieg is nobody's radical, but he doesn't quite represent the presidential status quo either. For all the ways that Buttigieg resembles the bulk of our white, male, Ivy League-educated presidents past, he stands out as a gay man -- one who came out in the middle of his 2015 mayoral re-election campaign and went on to win with 80 percent of the vote. For many Americans, this lends the Indiana mayor's presidential campaign an exciting kind of historic potential -- which is not lost on him. "Equality, to me, looks like a world where [a gay presidential candidate is] not newsworthy," Buttigieg tells me. "But I get that it is. I understand the importance and the sort of historic quality that could be attached to [my campaign] and the change that it represents."

Look no further than the reception to his campaign announcement in April -- specifically the moment when he shared a behind-the-podium kiss with his husband, Chasten, a moment that Mashable web trends reporter Heather Dockray celebrated as a "radical shift" in American politics. "When I started my career in office, it might've seemed like it was impossible to be out and elected, at least where I lived," Buttigieg says. "And now it is possible. Seeing how quickly that could change and realizing that I could be a part of changing it is something I'm very conscious of."

Buttigieg isn't the first queer person to run for president. Fred Karger, a longtime political consultant from California, sought the Republican nomination in 2012, and Joan Jett Blakk, a drag queen from Chicago, ran on the Queer Nation Party ticket with the promise to "Lick Bush" in that same 1992 election that Eileen Myles wedged her way into. But Buttigieg's campaign is arguably the most viable presidential run of any queer candidate thus far. "I've never seen anyone quite like Pete before," Karger says. "He is just so smart, so attuned to the issues, so relatable. He's got experience, great ideas, and an ability to really communicate those ideas, too, in a really straightforward, easy-to-understand kind of way. The fact that he's openly gay is just a giant bonus."

Karger isn't alone in his excitement for the Indiana mayor. Buttigieg's campaign has resonated with a lot of people who live beyond his mid-size midwestern city, thanks in no small part to a star-making CNN town hall event in March that catapulted the candidate to national attention. In early April -- while still in the exploratory phase of his campaign -- Buttigieg announced that he'd raised $7 million, clearing the 65,000 individual-donor threshold needed to qualify for the first Democratic National Convention debate in June. He has also come in third in at least two early Iowa caucus polls, just behind former Vice President Joe Biden and Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont.

For those who've been paying close attention, the rise of Pete Buttigieg -- or Mayor Pete, as some call him, perhaps to avoid mispronouncing his Maltese immigrant father's surname -- should come as no surprise. In a 2016 New Yorker profile, former President Barack Obama praised the Indiana mayor as a future leader of the Democratic Party alongside fellow 2020 hopeful Sen. Kamala Harris of California, and just last year both Politico and The New York Times ran stories about Buttigieg's White House ambitions, with the latter outlet wondering if he "might be president someday."

It's not totally clear how much this sudden media spotlight translates to genuine support from the Democratic base. Are the subconscious biases of a handful of journalists in New York and Washington -- many of them white, male, and Ivy League-educated, just like Buttigieg -- pushing the polyglottic ingenue to a position he's unqualified to fill? Slate staff writer Christina Cauterucci seems to think so. In March, she wrote an opinion piece critical of the attention news outlets have given Buttigieg while ignoring the record number of female candidates also seeking the Democratic nomination. Cauterucci, a queer woman, also critiqued the framing of Buttigieg's gayness as "a major win for diversity," arguing that Mayor Pete's whiteness, wealth, and maleness have likely trumped whatever setbacks our homophobic society might have dealt him. Author Jacob Bacharach was far less generous in his assessment of Buttigieg, writing for The Outline that Buttigieg's "palatable" model of queerness and hetero-assimilative presentation were straight up "bad for gays."

Buttigieg says he can't say for sure whether his being white and male has played a role in his campaign's success. "I honestly don't know," he tells me. "I know that white privilege exists, I know that sexism is a force in our politics to this day, but I don't know how much they add up or how much they have helped or hurt me in the primary or [how much they may help or hurt me] in the general." He declines to respond to Bacharach's charge directly, telling me that he tries "not to get too caught up" in every piece of criticism lodged his way because if you get "too absorbed, it can just drive you nuts." Pete's husband, Chasten, on the other hand, dismissed the idea that either he or Peter, as he calls him, aren't sufficiently gay. "Too gay, not gay enough -- that's a silly question," Chasten says. "We are two men married to each other. I think that counts as gay."

A 29-year-old teacher from Traverse City, Michigan, Chasten left his teaching job to focus on his husband's campaign, though he has picked up some part-time work at the South Bend Civic Theatre. He met Pete on a dating app in 2015. ("Possibly not the app you're thinking of," Buttigieg joked at a Victory Fund event in April.) They tied the knot last June in South Bend at the Episcopal Cathedral of St. James, coincidentally during the city's Pride Week festivities. "We got married and went to a block party straight from the church," Buttigieg says.

South Bend isn't the gayest city in the country, but it does have an LGBTQ+ community center and a handful of queer-friendly bars and events. Pete and Chasten say they're partial to Guerrilla Gay Bar, a venue-less event series that has hosted monthly takeovers of various straight bars in the area since 2012. "It's been pretty cool to watch how it's emerged over time," Buttigieg says. "We didn't have too many established gay or gay-friendly businesses, so they organized this takeover once a month to turn some bar into the official gay bar of the day. It gives the community a great place to gather. We're living in a very conservative state, but they've come together to support each other in a really beautiful way." Chasten adds, "It's like we're a little blueberry in raspberry Jell-O. A blue city in a purple county surrounded by red counties. There are a lot of pressures and concerns that come with being open in our community when people just a mile down the road from you might have dramatically different views about sexuality, religion, and politics."

Mayor Buttigieg's queer constituents have seen their ups and downs since he took office. In 2012, he fired South Bend's well-liked Black police chief, straining his relationship with the city's communities of color for years to come. He further strained that relationship three years later when he ordered 1,000 homes in South Bend's Black and Latinx neighborhoods demolished as part of his urban redevelopment plan. Such actions suggest a blind spot when it comes to race, one that's now playing out on a national scale. In April, Buttigieg came under fire for an old clip of him saying that "all lives matter," and he has also said that prisoners shouldn't be allowed to vote while incarcerated, a policy that would disproportionately impact Black, Indigenous, and Latinx Americans.

In the final year of Buttigieg's first term, the Indiana General Assembly passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which would have opened the door for anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination had it not been amended shortly after then-Governor Mike Pence signed it into law. Speaking of the current vice president, Buttigieg assures me that Pence's anti-gay religious fervor is for real. "[Pence] really believes a lot of this stuff," says Buttigieg. "I can't tell if he genuinely believes that Trump is a good president, but he does hold a lot of backward and extreme views about sexuality and science."

But queer public life has also improved in a lot of ways since the mayor took office. Not only has South Bend begun to celebrate Pride every June, but in 2012 -- three years before Buttigieg, himself, came out as gay in an editorial for the South Bend Tribune -- the city passed a civil rights ordinance prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.

Similar protections are gaining momentum in Congress at the moment. The Equality Act, introduced by Representative David N. Cicilline of Rhode Island, would provide federal protections for queer and trans people who experience discrimination -- protections that currently only exist at the state and municipal level, leaving a little over half of all LGBTQ+ Americans without legal recourse should such incidents occur. Though the Equality Act passed the Democrat-controlled House in May, advocates for the community worry that its passage in the Republican-majority Senate will have to wait until after the Democrats gain more ground -- like, say, during the 2020 general election.

Buttigieg supports the Equality Act, telling me that he'd sign it into law if he were president. While we're talking hypotheticals, I ask if he'd sign a version of it that dropped the trans protections, perhaps as a result of some kind of compromise with Republicans, just as the Employment Non-Discrimination Act's sponsors did back in 2007 with the Human Rights Campaign's support. Buttigieg says that he'd be "hard pressed" to sign such a bill, explaining that he'd only do so if it's what advocates for the trans community were asking him to do.

"We're not [where we should be] on gay rights, and we're that much further from where we want to be on trans equality," he says.

Beyond the Equality Act, Buttigieg is largely averse to discussing concrete policy in interviews. He tells me that he wants to reform the electoral college, the criminal justice system, and American health care, but he stops short of explaining how he might reform them. It's something that his critics have picked up on, this aversion to discussing policy proposals in concrete detail as some of his fellow 2020 hopefuls, like Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, are known to do. When asked about this criticism, Buttigieg defends his approach. "Good policy is almost never made exactly as it's promised on the campaign trail," he says. "The New Deal didn't come about because F.D.R. proposed it, got elected, and made it happen."

To Buttigieg, it's more important to know where a candidate stands and what their values are so that we can figure out what kind of policy they'll create once they're in office. His reasoning makes sense in theory, but it doesn't always pan out when put into practice. A lot of queer voters would probably like to know what Buttigieg plans to do about FOSTA-SESTA, considering how heavily the LGBTQ+ and sex work communities overlap. Every single one of his fellow Democratic candidates who were in Congress last spring voted for the anti-trafficking bill that has threatened the lives and livelihoods of sex workers nationwide. Specificity on this matter and how it might set him apart from his competitors would be much appreciated by many potential supporters. But the mayor demurs, calling for "a larger conversation" about sex work without starting that conversation himself.

"I'm not ready to make policy news on this yet," he says. "The reason FOSTA-SESTA moved so quickly is because [lawmakers thought] that by supporting the bill they were opposing the harms that come from sex trafficking. We now understand that this legislation harmed vulnerable people, but this needs to be part of a larger conversation about how we treat sex workers and all of the reasons why this society hesitates to embrace the idea of sex work. I don't think all of those ideas are wrong, but we need to open up debate about these policies, which were well-intentioned but harmful in practice."

That debate might open up as the race wears on -- maybe Buttigieg, himself, will be the one to do it. Sex work has come up in this election cycle, but it's still rarely discussed -- not surprising, considering the fact that presidential candidates and sex workers generally live under vastly different economic conditions. Our candidates are "always a john and never a hooker," as Zoe Leonard notes in "I want a president."

In our interview, Buttigieg criticizes Trump's pledge to "Make America Great Again" and nostalgia-driven politics more broadly. "Even if there was greatness in our past, there's no going back to it," he says. "So what does it look like going forward?" It seems we're still waiting on the answer.

Pete Buttigieg is one of three covers for Out's June/July 2019 Pride issue to celebrate Stonewall 50. The issue is also covered by activist Sylvia Rivera and actress Mj Rodriguez. To read more, grab your own copy of the issue on Kindle, Nook, Zinio, or Apple News+ today. Preview more of the issue here, and click here to subscribe.