Two years before her death, Stonewall veteran Sylvia Rivera served as muse for a photography series captured by Valerie Shaff. The black-and-white images feature the outspoken activist dolled up with razor-thin eyebrows, a bold lip, and wind-strewn hair on a makeshift encampment near the Hudson River. A nearly 50-year-old Rivera was living there in protest of the mostly gay- and lesbian-focused organizations and community groups at the time -- particularly, The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Community Center (then known as the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center Inc.), which was mere city blocks away.

Rivera contended that the mainstream LGBTQ+ organizations were ignoring the needs of local homeless youth and transgender people. For her, the LGBTQ+ nonprofit industrial complex had grown into something far different from the initiatives she'd spearheaded throughout her lifetime.

"Sylvia was really for the democratization of our movement. She was unwilling to have an agenda be set behind closed doors by the most elite people in the community," says Dean Spade, a trans activist and associate professor at Seattle University School of Law. "We see this even now: There are always battles over how homeless people and people with psychiatric disabilities are treated at LGBTQ+ centers and events. The battles over those exclusions are an example of carrying on Sylvia's work in a deep way."

When Rivera left the world due to complications from liver cancer in 2002, her work served as a bridge: on one side, the advocacy world dominated by gay men and lesbians who had historically excluded trans people; and on the other, an increasingly more vocal trans community and an uprising of trans-led organizations. For this next generation of activists, Rivera's groundbreaking creation of Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) and the accompanying STAR House represented one of the first major initiatives centering trans and gender nonconforming people in our community.

According to Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility edited by Tourmaline, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton, "Rivera and [Marsha P.] Johnson have especially been invoked by contemporary advocates working to imagine a world beyond today's neoliberal and homonormative social justice landscape." As the volume notes, there were other organizations at the time with varying degrees of radicalism in their politics -- the Queens Liberation Front, the Transvestite Legal Committee, and the Transexual Action Organization among them. Nonetheless, STAR has had the most enduring legacy.

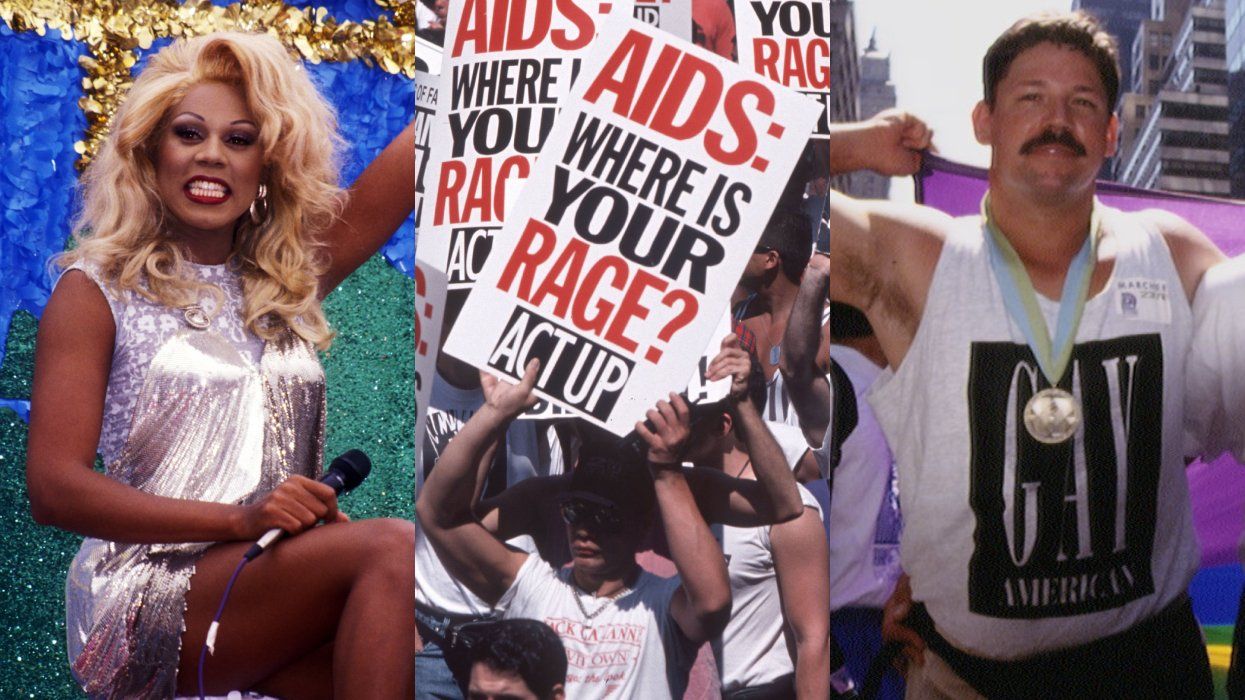

This is particularly notable, considering STAR's first iteration disbanded after the 1973 Christopher Street Liberation Day. During the march, which is a precursor to today's Pride celebrations, Rivera and her cohorts were heckled by onlookers and fellow participants, mainly gay men and lesbians who were unsupportive of STAR's organizing efforts. At the time, STAR (and the trans community in general) was deemed adjacent to the priorities of Gay Liberation, and organizers worried their inclusion would send the wrong message to the press and general public.

In fact, it wasn't just STAR that disbanded. "Sylvia left the movement after the first few years because she had been refused the right to speak after one of the Pride marches," says Randy Wicker, a longtime activist and late-in-life friend of Rivera's. "She left for 20 years."

But in 1992, when she learned of the mysterious death of her friend and fellow organizer, Marsha P. Johnson, Rivera was lured back into organizing work. Some eight years later, a 25-year-old transgender woman named Amanda Milan was killed by two men in the streets of New York. Milan's brutal murder, which occurred just before that year's Pride Parade, crystallized Rivera's enduring frustrations with the queer community: When Matthew Shepard was killed, his death prompted widespread outrage, organization, press outreach, television spots, and even legislative attention. Rivera, reignited, refused to let Milan pass without demanding the same outrage.

Following Rivera's lead, the trans community mobilized around Milan's murder, prompting an astounding 300 people to attend her funeral. Rivera, still unafraid to call out the transmisogynistic respectability politics of the cis gay elite, was disappointed that the Human Rights Campaign, now the largest LGBTQ+ advocacy group in the United States, hadn't taken up the often overlooked murders of transgender people as a worthy cause. "Trans people were very angry at the Human Rights Campaign. You don't realize how marginalized trans people were. HRC considered them a fringe group," Wicker remembers. "I don't think they had any understanding of gender identity and issues of freedom and gender expression." Tired of waiting for their reform, Rivera instead remade STAR. Milan's death became a symbol: tears shed transformed into a rallying cry.

Despite continued silencing and erasure from the larger landscape of LGBTQ+ nonprofits, Rivera fought fiercely in the last two years of her life. She continued to publicly excoriate the proposed Sexual Orientation Non-Discrimination Act (SONDA), which had been periodically introduced since the 1970s and failed to provide protections for trans people. Wicker recalls Rivera meeting with the Empire State Pride Agenda on her deathbed, pleading that trans people not be left out of the legislation. Ultimately, they were -- and gender identity wouldn't be included in the law until New York Governor David Paterson issued an executive order seven years later.

Within a year of Rivera's death in February 2002, the beginnings of a national network of trans-led organizations began to emerge. Transgender Law Center was founded in San Francisco in July of that year by recent law school graduates Dylan Vade and Chris Daly. A month later, Spade exalted the legacy of Rivera in the formation of the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, a multiracial legal aid organization centering trans, gender nonconforming, and intersex people who are low-income. While he was inspired in part by his own discriminatory run-ins with law enforcement and the legal system as a trans man, he also set out to enshrine the radical, intersectional approach to organizing and activism that Rivera utilized throughout her life.

"We designed our organization as a collective, using a horizontal structure. We don't pay lawyers more than we pay people who don't have a degree. We're focused on trying to actually build the political capacity of our movements and make change from [the most marginalized]," Spade says. "I think all of that work is in the vein of what Sylvia was asking for because she came from movements in the '60s and '70s that were very much volunteer-based, grassroots, and trying to build mass mobilizations."

In the next decade, more trans organizations and initiatives would find their footing, including the National Center for Transgender Equality. And now, more than 15 years after Rivera's death, the landscape of trans-led organizations across the U.S. looks drastically different. In fact, Borealis Philanthropy's Fund for Trans Generations (FTG), which supports trans-led initiatives, boasted supporting 93 groups and organizations in 2018. That same year, The Trans Justice Funding Project aided nearly twice as many specifically grassroots efforts.

Though often forgotten or completely erased, Rivera's impact far exceeds the lore and legend surrounding her involvement in the Stonewall Riots. Her decades-long commitment to building infrastructure for trans and gender nonconforming people to thrive has had a lasting impact on the world of organizing, on an almost molecular level. In any instance of trans social justice work, a fair question of measure would be, "What would Sylvia do?"

"Sylvia was a very disruptive person who entered movement spaces and demanded to be heard and wasn't afraid to break the rules, make people uncomfortable, and push for things that were unhearable inside some of the white-led gay and lesbian politics that were more dominant," Spade says. "The tradition of those kind of tactics are something we really hold on to by lifting her up and honoring her in all of her depth."

Eight months before her death, Rivera was invited to speak at the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Community Center, the institution that had once ignored her pleas for support on behalf of the trans community. In a signature moment of righteous defiance, as chronicled by Lawrence La Fountain-Stokes in the Center for Puerto Rican Studies' 2007 CENTRO Journal, she said, "The trans community has allowed the gay and lesbian community to speak for us. Times are changing. Our armies are rising and we are getting stronger. And when we come a-knocking -- that includes from here to Albany to Washington -- they're going to know that you don't fuck with the transgender community."

Correction: The final quote from Sylvia Rivera at the LGBT Community Center omitted a necessary attribution to Lawrence La Fountain-Stokes and CENTRO Journal for the original transcription and documentation.

Sylvia Rivera is one part of a triple cover for Out's June/July 2019 Pride issue, which also features actress Mj Rodriguez and presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg. To read more, grab your own copy of the issue on Kindle, Nook, Zinio or (newly) Apple News+ today. Preview more of the issue here and click here to subscribe.