I didn't immediately feel the absence of a life when I entered Aracelis Polanco's home in Yonkers, New York, on an early Friday morning in September. The home wasn't cloaked in shadows and despair -- in fact, the ceiling's bright fluorescent lights mixed seamlessly with the sunshine emanating through undrawn window curtains. There was a surge of everyday energy stirring among the inhabitants: the hustle and bustle of Polanco's youngest son, Salomon, shuffling out of the front door to his first job of the day, and the adorably ferocious yips and yaps from the resident terrier, Dercy. I was receiving frantic texts of reassurance from the eldest daughter, Melania Brown, that today was still a good day for a cover shoot despite her morning ritual of dropping her children off at school. These were textbook examples of life going on after tragedy.

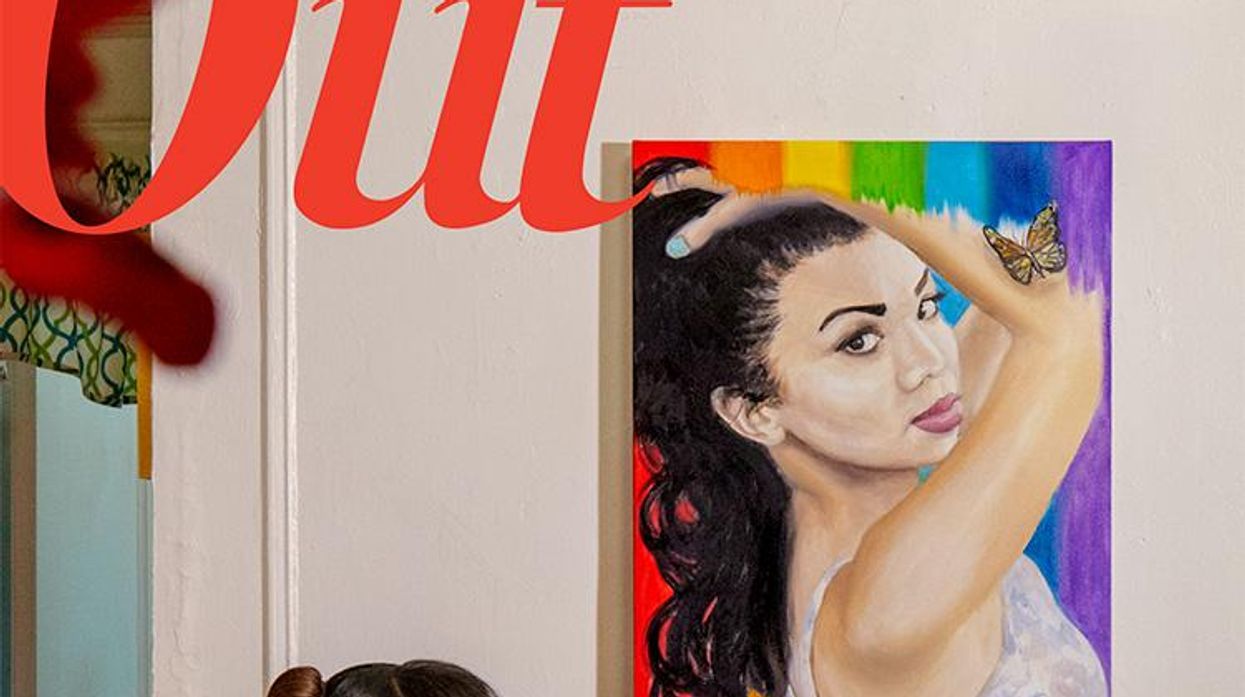

I sat on a chair at the glass table in the olive-green kitchen, noticing how the plants and the stacked china dishes covered its surface like a crescent moon. Then, I examined Polanco's face: her wise, gentle eyes, beaming smile complete with a signature gold crown, and a slicked-up church-worthy hairdo. She was gazing out the window, overlooking a mostly unobscured view of the upper Hudson River.

"This used to be Layleen's favorite seat -- right here in front of the window. She would sit there for hours and just look out," Polanco says placidly. No doubt, she's still mourning the loss of her daughter, Layleen Cubilette-Polanco, a 27-year-old transgender AfroLatina who died from an epileptic seizure while held in solitary confinement at New York City's Rikers Island in June. But in this moment, I see something powerfully familiar: a kind of unfathomable resolve that mothers of color are known to exhibit, an ability to make peace in moments of extreme pressure.

It's been a busy 24 hours for the Cubilette-Polanco household. On the night before our shoot, Layleen's family -- which includes an assortment of chosen relatives, like her community mother, Ashley Chico (known as Leslie) and the ballroom House of Xtravaganza -- were given the 2019 Courage Award by the Anti-Violence Project. In an effort to squarely place in perspective the ongoing epidemic of violence against trans women of color, Dolores Nettles, the mother of Islan Nettles, a Black trans woman who was killed in August 2013, was also honored.

What binds these two families together is an unwavering devotion to keeping their loved ones' stories alive and seeking justice for the crimes committed against them. However, this kind of familial support isn't always the case when a trans woman of color is killed. In fact, it isn't uncommon for these women to be further degraded in death, willingly or ignorantly, by families that may not have fully understood or respected their womanhood. A burial in masculine clothing that they might not have chosen for themselves, potential misgendering in their obituaries, a reference to names they may have long discarded, and further estrangement -- this is what many can expect in passing on. But Mama Nettles is different, and so are Layleen's loved ones. This was made clear during the speech that Melania, the designated media spokesperson for the Cubilette-Polanco family, gave that evening.

"My family and I are extremely grateful for the individuals that have been here from day one of this unimaginable and unexplainable pain. You gave me a platform to fight for my Layleen and all the other Layleens that are still alive," she said. "Thank you all for keeping my baby sister, our human, alive. We still have a lot of work to do, and I'll be here every step of the way -- and always remember the only difference between you and them is that you have the courage to be you."

When Layleen Cubilette-Polanco's death began making waves in the media in early June, she was the 10th Black trans woman reported dead in state custody or killed in 2019. Just three days later, the American Medical Association, the leading national physician organization in the country, declared that there was an "epidemic of violence" plaguing trans women of color. AMA Board Member S. Bobby Mukkamala, M.D., released an official statement, saying, "According to available tracking, fatal anti-transgender violence in the U.S. is on the rise, and most victims were Black transgender women. The number of victims could be even higher due to underreporting, and better data collection by law enforcement is needed to create strategies that will prevent anti-transgender violence."

Curiously, the criminal justice system that's expected to deliver solutions by the AMA is the same one that allegedly led to Cubilette-Polanco's demise. Unfortunately, the young trans woman of color's journey to Rikers Island was a winding one. In 2017, she was arrested in a New York Police Department sting operation, in which undercover police officers solicited her for sexual acts in exchange for money, according a report in Vice. After allegedly consenting, she was arrested and found to be in criminal possession of a controlled substance.

Soon after, Cubilette-Polanco's case was directed to the Human Trafficking Intervention portion of New York City's Midtown Community Court, which aims "to promote a just and compassionate resolution to [sex trafficking] cases -- treating defendants as victims who are often in need of critical services." However, due to three missed court dates and a 2018 arrest, she would receive a round of bench warrants, which grants police the power to arrest a defendant for violating court rules.

On April 16, Cubilette-Polanco was arrested again on misdemeanor charges related to an alleged assault of a cab driver after refusing to pay a fare in New York City's Midtown neighborhood. Three days later, she was released of those charges, but was held for failure to pay a $500 bail due to the prior bench warrants issued against her.

By the time of her death on June 7, Cubilette-Polanco was being held in custody at the Rose M. Singer Center, an all-female facility on Rikers Island, for nearly two months. According to reports received by David Shanies, the lawyer representing Cubilette-Polanco's family in a lawsuit against the city and several jail staffers, she was placed in solitary confinement for 20 days after a fight with another inmate, despite her medical history of epilepsy and schizophrenia. During her time at the facility, Cubilette-Polanco alerted prison officials of her mental disorders and was prescribed medication to alleviate the impact of her epilepsy. Still, she suffered at least two seizures while in custody.

"The epilepsy is the much more obvious condition that should have made her ineligible for solitary housing, but somehow, a physician who works for the Department of Corrections was specifically asked whether it was medically acceptable to place her in [there], and said, 'Yes,' for reasons we can't fathom," Shanies says. The medical reports state that Cubilette-Polanco had been neglected in her cell despite correction officers noticing her body lying motionless. She even missed a scheduled group therapy session, and when doctors and mental health staff visited, they were assured by those same officers that she was simply sleeping.

"There was a multi-hour period where she was not accounted for, her condition was not accounted for, and finally someone had the sense to say, 'What's going on in there?'" Shanies says. "By the time they opened the cell, she almost certainly had been dead for quite a long time, because the emergency responders said they found her body cold to the touch -- which suggests that she had died quite a while before they actually got to her, and the autopsy results concluded that she died from complications of her seizure disorder."

At the crux of Shanies' argument in the family's lawsuit is the notion that Cubilette-Polanco should never have been held in solitary confinement given her mental health status, and that her treatment amounts to "deliberate indifference," or when a professional knows of and disregards an excessive risk to an inmate's health or safety. There is research to support this stance. According to Solitary Confinement: Effects, Practices, and Pathways Towards Reform edited by Jules Lobel and Peter Scharff Smith, prisoners in solitary confinement disproportionately suffer from negative symptoms like sleeplessness, cognitive dysfunction, hypersensitivity, and anxiety.

Furthermore, experts like Juan E. Mendez, a former United Nations Special Rapporteur, have found that the practice "can amount to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment," especially for juveniles and people with mental disabilities. In other words, being a trans woman of color caught up and isolated in the criminal justice system only compounded the circumstances facing Cubilette-Polanco.

While incarcerated, her family and loved ones were in the dark about her whereabouts. If she were suffering in those prison conditions, alleges her lawyer and family, it's likely she couldn't adequately advocate for herself. Without her family being notified of her status, Cubilette-Polanco had limited options of recourse. According to her sister Melania Brown, Cubilette-Polanco called on Mother's Day after weeks of being absent, assuring Aracelis Polanco not to worry and that she would "be home in a few more days."

"I did not even know my sister was arrested. I didn't know she was in Rikers. I didn't even know there was a bail. If I would've known these things, my sister would have still been alive today," Brown says. "I called up my brother a week before she passed and I'm like, 'I've been trying to call her phone. She's not answering. Mommy keeps telling me she doesn't know where she's at.' It's not [like] my sister to do that, especially with me. We were unbreakable."

Cubilette-Polanco's family learned of her ultimate fate when correctional officers showed up on her mother's doorstep. Soon after, her family contacted Brown, who then called Rikers and learned about the autopsy and other records. The next course of action was to identify Cubilette-Polanco's body. "I just cried. I can't even explain the feeling. I still can't grasp it. I still can't believe it. Sometimes I go with very big denial," Brown says. "It was very, very, very tough. I just couldn't believe that she was gone."

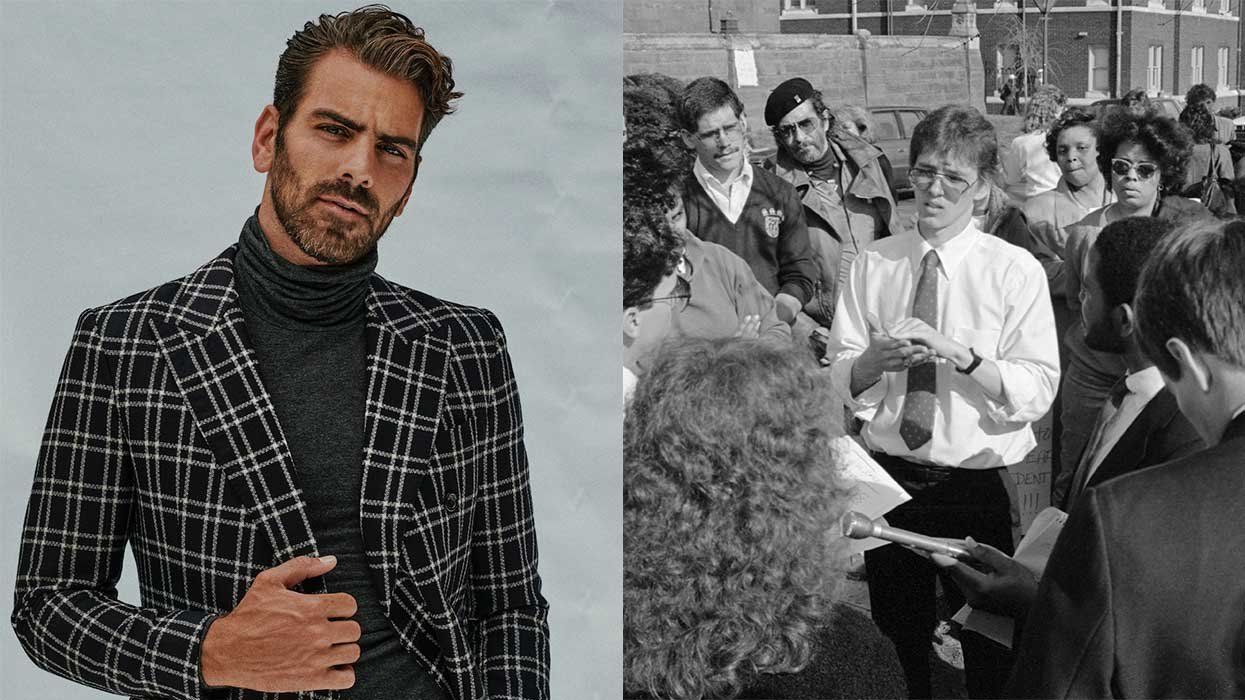

Though she died alone, Layleen Cubilette-Polanco was loved. Days after initial reports shared her story with the public, the New York City Anti-Violence Project gathered her family and more than 600 people at Foley Square in New York City. On that drizzly afternoon, while #Justice4Layleen lit up the internet, Melania Brown delivered a moving speech, loved ones from the House of Xtravaganza shared their grief, and transgender activists of color like Cecilia Gentili, Hope Giselle, and Pose actor Indya Moore shared their condolences.

"Layleen Polanco, the most recently slain trans woman of color, a Black trans woman. I looked up to her," Moore said at the rally. "Just wanted to say, you know, when you're a young trans person, you have the trans women and people around you to look to when you imagine where you want to see yourself in your life. Layleen was one of those girls for me." Beyond Moore, Cubilette-Polanco was revered by her two House of Xtravaganza daughters, Alana Ramos and Christina Yates, and her own community mother, Ashley Chico. Cubilette-Polanco would sometimes steal away from her mother's home and retreat to Chico's apartment where she'd soak up advice on her transition and the ways of the world.

"Layleen was very free-spirited and she was a light. She would enter the room and just make me smile, even in her youth," Chico shares. "She just wanted to do good all the time. She was good to a fault. She had a good heart. A little naive, but that comes with age, right?"

For Melania Brown, reminiscing about moments with her sister often invokes a mixture of laughter and tears. Just three years apart in age, the two were so inseparable that she swears, "We couldn't use a bathroom with only one of us being in there." Brown shares a number of stories in which she is the more laid-back, mature one and Cubilette-Polanco is the spunky life of the party. But her favorite story, and one that speaks to her sister's wisdom, happened at a difficult time in her life.

"I was depressed. I even tried to commit suicide and all that. I was extremely overweight and I was just disgusted with myself. And I went to go see [Layleen] because I just needed her at that time," Brown shares through tears. "And she looked at me and she said, 'There's nothing wrong with you. I love you just the way you are. You are perfect in my eyesight. If you feel like there's something that you need to change for you, then change it for you.' And she just gave me the strongest kiss on my cheek. I still feel that kiss and warm hug."

It was this three-dimensional depiction by family and friends that pushed Cubilette-Polanco's loved ones to share her story. And it reverberated through the media, largely due to the continued efforts of AVP. Since the initial rally, the organization has mobilized advocates and allies around her case at another rally later in June, and seeks to provide court support for her family's lawsuit against the City of New York. Cubilette-Polanco's story has also been mentioned on a national stage by politicians like NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and Democratic presidential hopeful Sen. Elizabeth Warren.

"I think Layleen's case got a lot of the attention that it did for a few reasons. It came in the middle of this epidemic of violence and death of trans women of color and in the middle of Pride Month," Shanies says. "It really hit the intersection of so many issues that desperately need our society's attention, from overcriminalization of sex work, to solitary confinement, to bail reform, to the mental healthcare and healthcare in general for inmates, and healthcare, particularly for transgender inmates and those with disabilities. And Layleen was a compelling personality, how loving and beloved she was. When people got to know about her, her story became all that more compelling and all that more tragic."

Melania Brown understands the importance of keeping Layleen's story alive, so she invited the Out team to document her family and enshrine her sister in print. On this particular day, which coincidentally would have been Layleen's 28th birthday, her mother, Aracelis Polanco, Brown, niece Aliyah, community mother Ashley Chico, and family friend, Amanda Collazo are sharing their favorite memories. There's little room for tragedy here; it's a celebration. Brown shares how Layleen's stellar sense of humor always brightened up even her darkest days, like when Brown's marriage ended a few years ago and Layleen encouraged her to go out to a local club and dance. Other women chime in with some of their recollections, giggles and warmth filling the room.

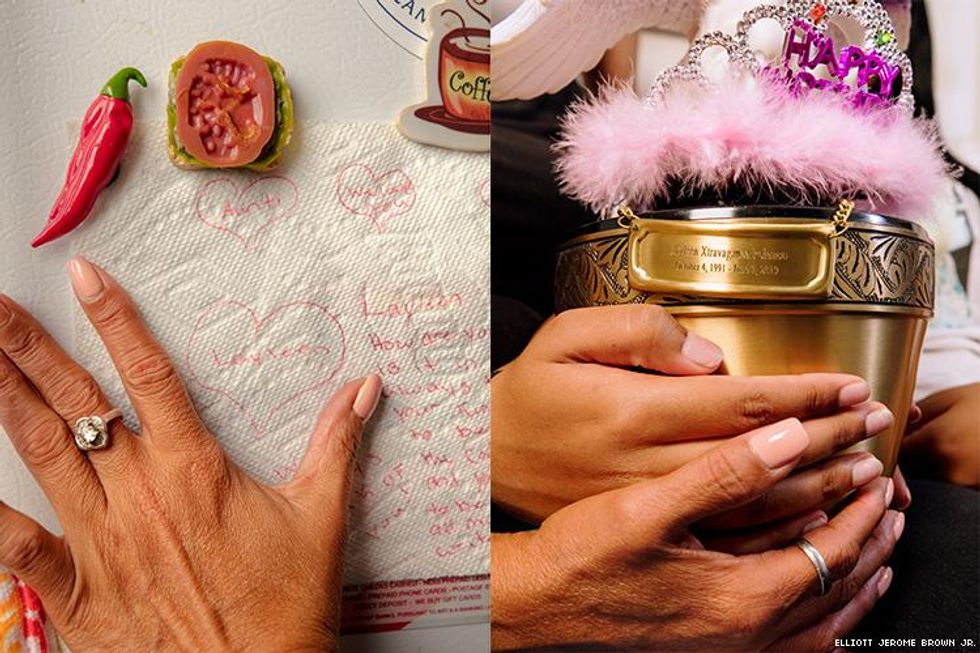

Then, Polanco reveals that she packed up all of the things Layleen left behind. She disappears for a few minutes, and re-emerges pulling a large, bulging, black suitcase behind her. She lays it out on the floor of her bedroom and gingerly unzips it. "Wait...you kept all of this," Brown says to her mom in disbelief. Polanco beams, yet again, as she watches the younger women tear through the suitcase, scrambling for pieces of their loved one. There's a small bottle of hairspray and a used electric toothbrush, a travel-size Secret deodorant stick, and a batch of blankets -- and, of course, there are so many clothes. At one point, Collazo holds up a slate-colored T-shirt that reads, "I'M GRRREAT" to her nose, taking in the remnants of Layleen's scent.

As the tender scene plays out in Polanco's room, I notice the small round wooden table that's become an altar for Layleen. There's a poster that serves as a backdrop for the space of reverence. It contains an image of the beautiful young girl with her glorious dark locks and a determined grin. Above her head

is a quote from Assata Shakur's autobiography: "You died. I cried. And kept on getting up. A little slower. And a lot more deadly." A number of objects eclipse the table's surface: Layleen's golden urn (topped with an iridescent-colored unicorn figurine), two prideful rainbow mugs, a saucer with a quarter of a breakfast sandwich on it as an offering to her spirit, the just-won award from AVP, and the piece de resistance -- a tall, white candle, with a strong and steady flame.

"I want everyone that had something to do with my sister's death to be held accountable. I'm not giving up. They go home to their loved ones, and I feel empty every single day, watching my mom and hearing her cry out for her child," Brown says. "I'm not going to stop until justice is served. I'm coming for justice, and I'm going to get it."

This story is a part of the 2019 Out100 Trans Obituaries Project. Read the full package here.

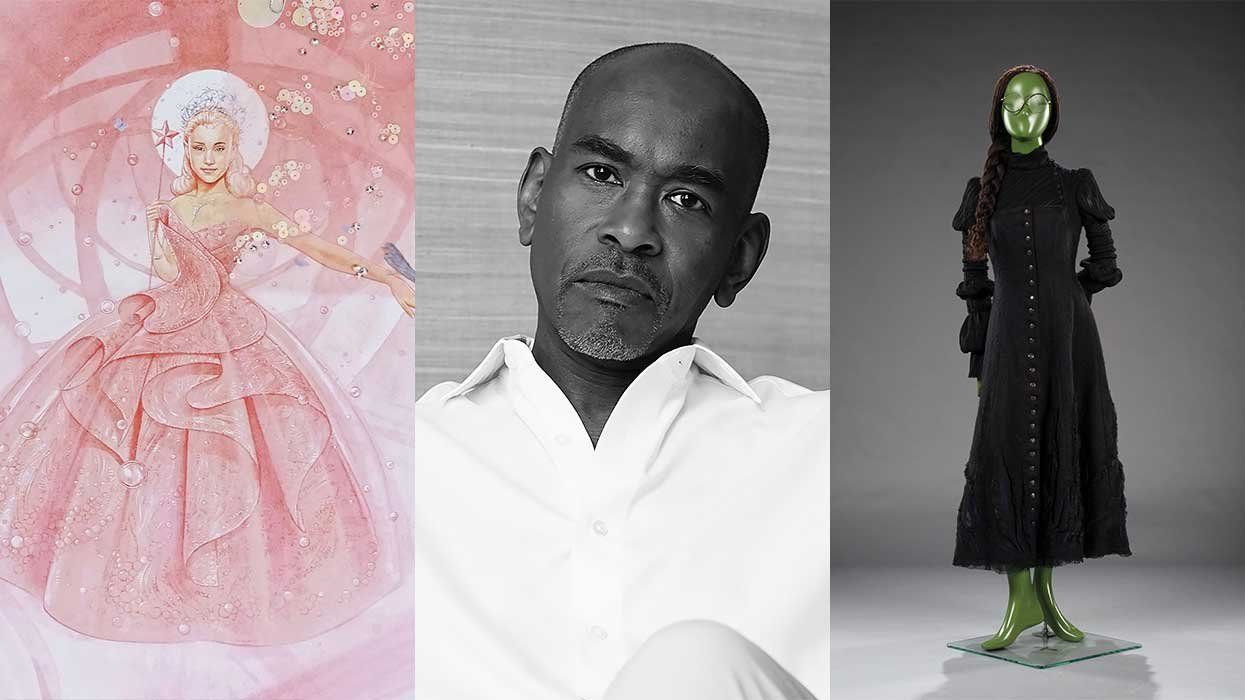

Photographed by Elliott Jerome Brown Jr

This piece was originally published in this year's Out100 issue, out on newstands 12/10. To get your own copy directly, support queer media and subscribe -- or download yours for Amazon, Kindle, or Nook beginning 11/21.