"Give me the details," Cole's best friend, Alec, demands after Cole comes back from a date. Cole taunts him a little: "You want to know what movie we saw?" Like a practice round of phone sex--in this case, two 17-year-olds instant messaging--Cole won't dish until Alec says what he wants: "The dirty parts."

Daniel Handler's new novel, All the Dirty Parts, is true to its name, heavy on the short staccato reports of Cole's sexual adventures, light on feelings from its fuckboi narrator. A certain wonder exists between its explicit descriptions, and though Cole's more concerned with his litany of conquests, it's clear he's left a trail of carnage.

Alec is Cole's first challenge to this fucking-or-feelings bifurcation. They swap porn links they think the other will like, with Cole selecting for Alec clips with two guys and a girl. "Everybody thinks something is hot," Cole says blithely. When they graduate from watching porn to messing around on Alec's bed, Cole's flash of apprehension is outweighed by desire: "It feels so good, prickly on my skin when I think about it, and fucking hot when I don't."

With no other girl on the immediate horizon, this exploration escalates, and recurs--it's an experimentation that Cole both craves and callously evaluates as his best available option. Alec wants to try, he says. And even though Cole's default is detached jerk, he knows they're talking about two different things, saying, "I'm trying it like, you find a coin on the table and you spin it for no reason but to see it happen. He's trying it like medical school, because maybe he'll grow up to be a doctor." Alec says he's bi; the most Cole can cop to is horny.

And then Cole meets a wild, exotic, elusive girl--his match really--and cruelly drops Alec, quickly shoving aside his momentary confusion: If he was a girlfriend, I would try more, Cole thinks. But--he is not, not, not my fucking girlfriend.

This is Cole's story, but Alec gets the happier ending: After the girl has discarded Cole and, worse, made him feel, Cole is alone. Alec has a boyfriend. He's happy. He walks away from Cole.

The novel is shocking in how little it--or the author, whose Unfortunate Events children's series has sold some 60 million copies and spawned a major film and a Netflix series--cares if you are shocked by it. It's been more than 40 years since another famed children's author, Judy Blume, got herself on the most-banned list with Forever... . "It doesn't actually seem tame now," says Handler, who recently reread the book and was struck by both the significant age gap between the lead character and her older boyfriend and her parents' encouragement of the relationship. "If you changed a couple of names and submitted it to publishers, it would be roundly dismissed," he says.

That's because even with the ubiquity of online porn accessible to teens, you won't find much sex in books for or about young adults--All the Dirty Parts isn't even classified as part of the booming YA market but rather as erotic literature. "I think the chances of it ending up in high school libraries are really slim," Handler admits, "but I think it is going to reach a population that's not really looking at how a book is marketed or labeled."

Handler is hardly new to the industry or the understanding that there's a gap between what authors write and publishers buy, but he's still frustrated by the fear of blacklisting by reviewers, educators, or librarians, which results in novels about teenagers and sex that are either judgy or bumbling. "You don't see a lot of books with young people having sex and feeling pretty good about it--and of course that happens a lot."

He's also angry about the double standard. His queer writer friends tell him editors get nervous or shut down their attempts at LGBTQ coming-of-age tales from the start. "There's increasingly a lot of queer narratives, which is great to see, but in terms of the actual down-and-dirty physical encounters, they're almost always treated very gently or not at all," Handler says. "Being terrified of queer sexuality is in and of itself a phobic response. It's a bummer to think about--[that there are] people dealing with queer young people who think, The one thing I don't want them to read about is sex."

For all its relentless heterosexuality, the origin for All the Dirty Parts was actually queer. At a dinner party, a gay friend of Handler's told him about an upcoming trip home when he'd see all his ex-boyfriends--and their wives. "So often the first relationships between bi and gay men are with straight men," Handler says. "It seems like a near-universal situation for so many men I know."

Handler counts himself on the straight(er) side of that same story. "I always describe my sexuality as married because I am in a monogamous relationship with a woman that began in 1992," he says. (His wife, the illustrator Lisa Brown, is a sometime collaborator.) "Before that I did a fair amount of traipsing around on one end or another of the gender line, but with the exception of a few self-righteous months during my undergraduate days, I never thought it was worthwhile to identify as queer. That just felt self-aggrandizing to me. I think for a man in his 40s to say he's bisexual because of increasingly distant experiences just seems show-offy."

Handler's new book was published at the tail end of the summer, just as buzz began to ramp up for the new movie Call Me by Your Name, a study in queer desire based on the novel of the same name by Andre Aciman, who is also married to a woman. The book's sex scenes are immaculately rendered, and acutely resonant. For Aciman it's a way to explore a familiar theme in a way that feels fresh to him. "I've written several gay characters [in my books] because there are no real boundaries, like an unexplored land that allows me to let my imagination go and take all kinds of risks without fear," he says.

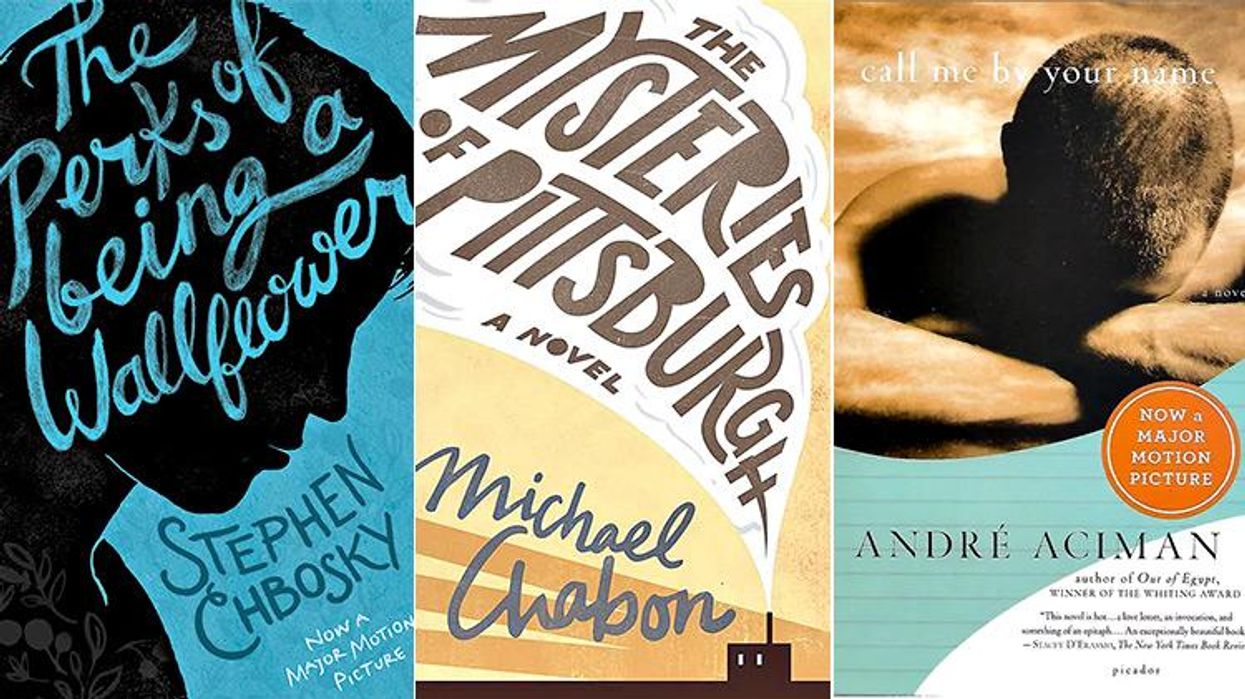

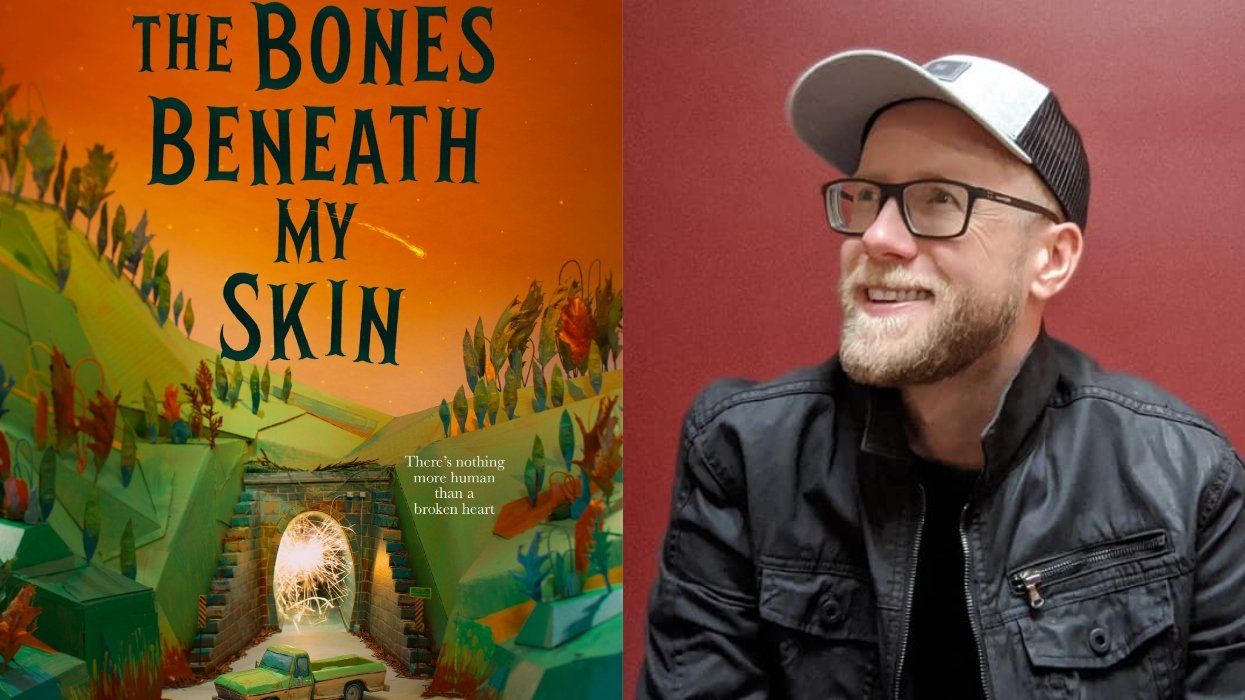

Related | Stephen Chbosky Explains Why 'Perks' Had to Be PG-13

When I interviewed Stephen Chbosky for Out's 2012 cover story about the film of his autobiographical 1999 YA classic, The Perks of Being a Wallflower, which features a proudly out teenage boy who shares a sweet kiss with his best friend, he said he'd literally never been asked if he was gay.

"I'm basically a straight boy," he shyly admitted, albeit one whose kinship with his gay friends helped heal his own traumatic childhood.

Meanwhile, Michael Chabon's debut novel, The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, was so earnestly queer--as were significant through-lines in his follow-ups Wonder Boys and the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay--that many assumed the author was gay, though he's been married for decades to writer Ayelet Waldman. In a 2005 New York Review of Books essay about Mysteries, Chabon casually wrote: "I had slept with one man I loved, and learned to love another man so much that it would never have occurred to me to sleep with him."

These books occupy a rare space in literature and queer culture, with their authors neither denying their characters' or their own same-sex experiences nor claiming them as definitive, endgame identities. They also resist diminishing the importance of youthful exploration or writing it off as a childish phase. Instead they describe sexual boyhood experiments with an almost tender regard--even if their own narrators, like Cole, can't yet understand or appreciate their lifelong significance.