Dwayne Johnson, (when alone, think "The Rock") should have won an Oscar last year for the Michael Bay film Pain & Gain where he played ex-con Paul Doyle, a musclehead torn between homosexual panic and roided-out religious guilt. The Rock lent the complicated character his usual bonhomie which humanized the story of modern greed and ruthlessness. Pain & Gain's satirical, daytime noir created an ethical contemporary moral myth--the kind missed-out by Scorsese's overscaled decadence in The Wolf of Wall Street.

In the new Hercules, a comic version of the Greek myth (adapted from a graphic novel by Steve Moore), The Rock stays solidly bemused, but the film itself is torn--between genre panic and erotic guilt. That's to say, this Hercules seems uncertain about being a straight-ahead adventure flick or slightly a parody. By turning The Rock into a Greek god, it becomes a version of the myth that rings new changes even on Hollywood's unacknowledged Sword & Sandal sensuality.

SLIDESHOW: HOLLYWOOD'S HERCULES THROUGH THE DECADES

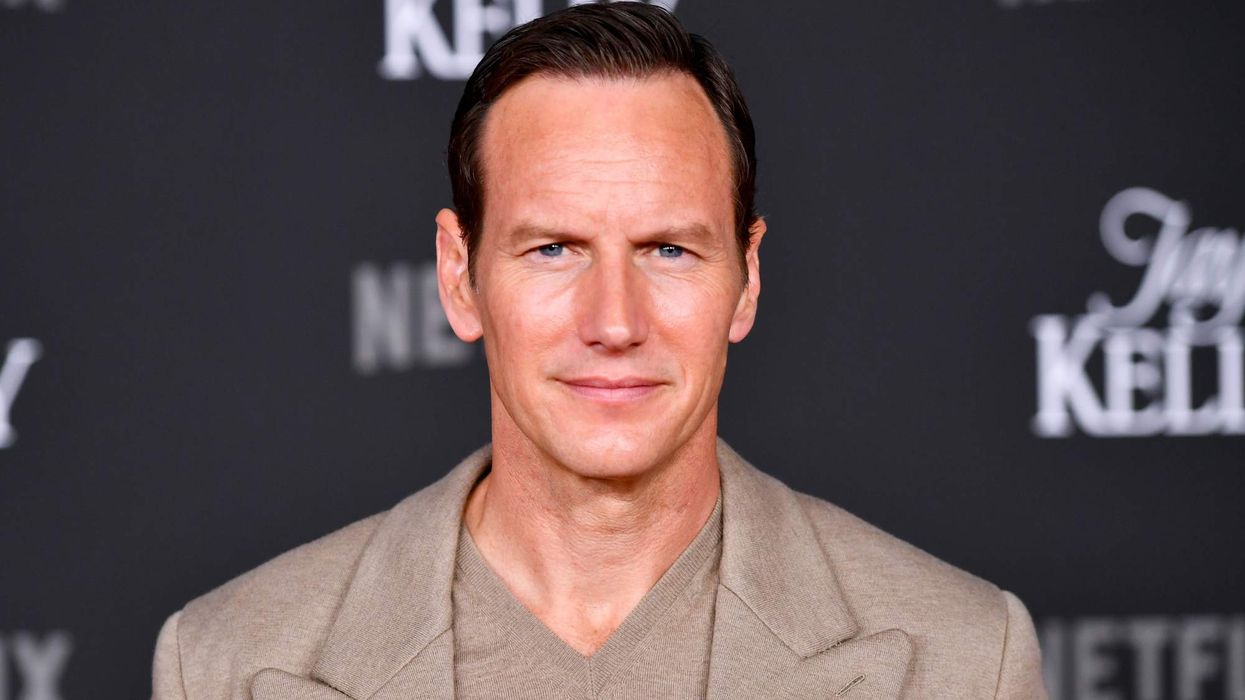

As The Rock maneuvers through the pretend-epic plot, he flexes actorly tone the way bodybuilders flex muscles. It's a casually comic, occasionally hot, sight but the first Hercs, Steve Reeves, Mickey Hargitay, Alan Steel (Sergio Ciani) Hercs all naturally had more stroke appeal. Later Hercs--Arnold Schwarzenegger, Lou Ferrigno, Kevin Sorbo, and Paul Telfer--had less of that innocent sensuality; they were just unassuming--as were their lackluster films and TV shows.

None of the previous Hercs had The Rock's wall-of-man immensity--he's an actor who doesn't need 3D--plus he holds his own among this film's roster of British thespian-mercenaries (John Hurt, Joseph Fiennes, Ian McShane, Rufus Sewell, Peter Mullan).

The Rock's mercurial, on-screen ease defines a more ordinary Herc--less superhero than a mundane figure from human antiquity (the Game of Thrones curse). The Rock wears Herc's wolf's-head hood and costume very well; not just a loin cloth, the look's almost couture--better dialogue might have made it seem chic, like Pharrell's Canadian Mounties Stetson hat.

A radically dressed Herc is part of a modern cultural adaptation signified by The Rock's emergence from the world of wrestling into movies as an icon of black and Polynesian background. The change isn't much different from the Germanic Kellan Lutz in last spring's The Legend of Hercules--Herc remains, after all, a figure of Western legend. The Rock's performance in this film represents an advance in masculine sexual iconography by including multiracial features, skin tones, and subtle ethnic echoes.

This new Herc parallels Kellan Lutz's blondined Herc, praised by critic John Demetry in his new book, Watch the Throne. Demetry notes the "perverse core" of director Renny Harlin's recently released The Legend of Hercules, citing how it "unfashionably conflates humility and power, masculine beauty and goodness"--a far more serious endeavor than director Brett Ratner's workmanlike action tropes with The Rock.

It is The Rock himself who, by taking on a role usually limited to European types, helps broaden awareness of gender icons and idealized figures of male sexuality. Hercules is a minor film but The Rock's image recalls the breakthrough made by legendary Hollywood photographer Georges Hurrell who, in 1929, posed Mexican actor Ramon Navarro for a landmark series of mythological portraits: one as the Knight Percival shown contemplating his own sword and, another of Navarro, in the signature softly erotic Hurrell style, wearing a crown of laurel leaves. Hurrell titled it "The New Orpheus."