By the time activist Phill Wilson stood in front of the International AIDS Conference in 2012 as an opening plenary speaker -- immediately preceding then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton -- he hoped the reason behind his founding of the Black AIDS Institute had finally changed. Maybe by now, 13 years later, he thought, the amount of effort and resources put into ending the epidemic in Black communities would mirror that invested into white ones. But it was, unfortunately, still "a tale of two cities," he said: the best of times for some, and the worst for others.

Seven years after that address, as Wilson's Los Angeles-based advocacy group celebrates its 20th anniversary, this divided reality persists. "The largest percentage of people in the world living with HIV, at risk for HIV, or even dying from HIV are of African descent. [But] if you were to follow the national or local television media in this country, what you would observe is that HIV continues to be a white gay disease, even though the data doesn't back that up," Wilson says.

According to the CDC, Black people account for a higher proportion of new HIV diagnoses. In 2017, while they accounted for just 13 percent of the United States population, they were 43 percent of the new HIV diagnoses. Sixty percent of those who received an HIV diagnosis were gay or bisexual men. "If you are not successful at ending the AIDS epidemic in Black America, you will not be successful in ending the AIDS epidemic in America, period," Wilson says.

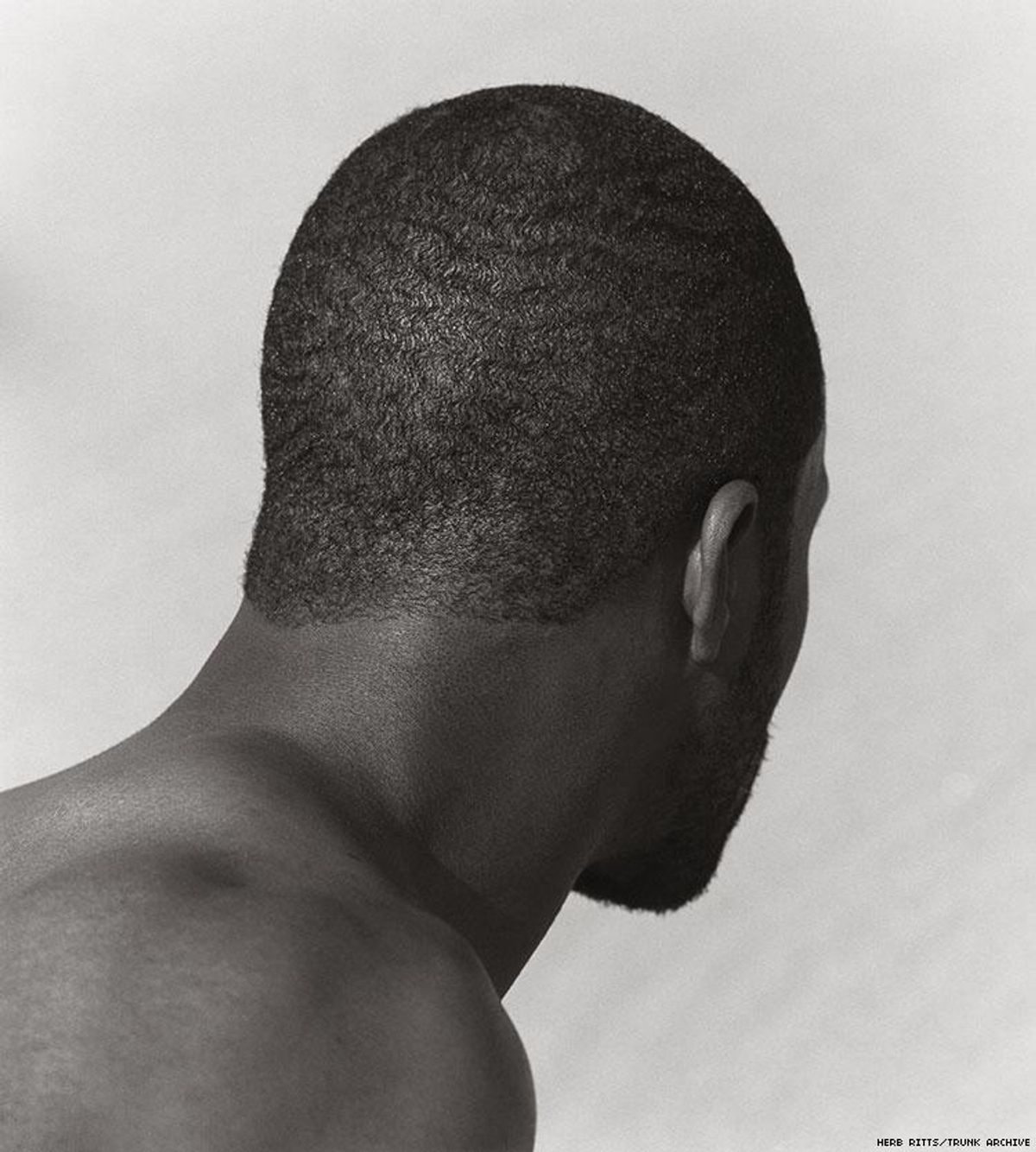

Wilson was introduced to HIV/AIDS in the early '80s, when it was first called gay-related immune deficiency, or GRID. He and his partner Chris Brownlie had swollen lymph nodes, a symptom that was prevalent in gay communities nationwide and, in a matter of weeks, led to the deaths of many in their Chicago, Black gay circle. After moving to Los Angeles, the couple became advocates as men living with HIV.

Brownlie died in 1989 of AIDS-related complications, and Wilson continued his advocacy, taking leadership posts for the city and county -- until 1996, when he got sick and was given 24 hours to live. He eventually recovered, thanks to the drug Crixivan (which had just received FDA approval), and returned to movement work in 1998 with the revelation that "enough [wasn't] being done in Black communities." That led to the founding of what would become the Black AIDS Institute, one year later.

Still the only national HIV/AIDS think tank focused exclusively on Black people, the institute's mission is to stop the epidemic in Black communities by engaging and mobilizing Black leaders, institutions, and individuals from a uniquely and unapologetically Black point of view. On the national level, the institute helps train health departments and support capacity building in health-related organizations aiming to serve Black people. They also consult on and advocate for inclusive government policies. Locally, with clinics located in Los Angeles' Black communities where health services are needed but not easily accessible, the organization provides holistic support, including family practice, dental services, and primary care. The institute also hosts support groups that look at risk reduction and HIV prevention from a social point of view.

Last year, it was announced that Wilson planned to retire, after more than 20 years of service to the movement. Now, as the organization charts its move forward, a new CEO, Raniyah Copeland, says there's much more work still left to be done. "It's now really about responding to the whole person," she says. "For Black people, the reason we face a higher risk of HIV is not because we have more sex. It's not because we inject drugs more than anyone else. It's because of these systems of oppression that we live in."

Copeland notes that the root causes of HIV are closely "linked to and fueled by" issues like mass incarceration, poverty, homophobia, transphobia, and racism. "So how can we, as activists, make sure that when we're talking about HIV, we're not leaving out what the root of the problem is and that our strategies and solutions are deeply rooted at structures that oppress Black folks?"

The answer for Copeland lies in intentional coalition building, and she hopes her personhood -- as a Black, cishet woman -- will aid in this process, especially as the institute continues reeducating communities that HIV doesn't only impact LGBTQ+ people. She also must continue the work of dismantling the deeply entrenched (and, in some places, legislated) stigma in pursuit of community-wide solidarity.

"We're all impacted by HIV in the Black community," she explains. "I hope that who I am is able to speak to other folks and show that this is not something that just gay folks need to be cognizant of." That also means making sure that "when we say women, we're talking about cis and trans women, being inclusive, and centering folks who are heavily impacted," she adds. (Sixty percent of HIV diagnoses in women occur among Black women.)

Recent headlines about HIV research and the potential for a cure are "exciting," Copeland says, but she's also cautious, considering the existence of tools "that could resemble an end to the epidemic that we're not maximizing" use of. Take, for example, pre-exposure prophylaxis (or PrEP), which we know Black and brown communities aren't using as much as their white counterparts.

Donald Trump's plans to end HIV, as announced during his State of the Union address, aren't helping as Copeland tries to navigate "how we make sure this president, who has been racist and homophobic and transphobic in his words and policies, doesn't develop a strategy to end the epidemic that won't include Black communities."

Over the past two decades, the Black AIDS Institute has shown that eradicating HIV sometimes means different methods of outreach and strategies for treatment or prevention. With Black Americans, Wilson suggests, the traditional toolbox can often be futile. "All the tools in the world are worthless if people don't have access to them, understand how they work, or believe that they work," he continues. "And right now in Black communities, in poor communities, communities in the South, other marginalized communities, people neither have access to these medications, nor do they understand them -- and often they don't believe they work. So you have to solve that problem, too."

"If we have any hopes of ending the epidemic, we have to follow the demographic data and allow that to form how we prioritize," Wilson adds. "There's a lot of talk about an AIDS-free generation, but we should not be exploring options that leave folks behind."

This article appears in Out's June/July 2019 issue celebrating Stonewall 50. The three covers feature the complicated candidacy of presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg, the enduring legacy of activist Sylvia Rivera, and the triumphant star power of actress Mj Rodriguez. To read more, grab your own copy of the issue on Kindle, Nook, Zinio or (newly) Apple News+ today. Preview more of the issue here and click here to subscribe.

Beware of the Straightors: 'The Traitors' bros vs. the women and gays