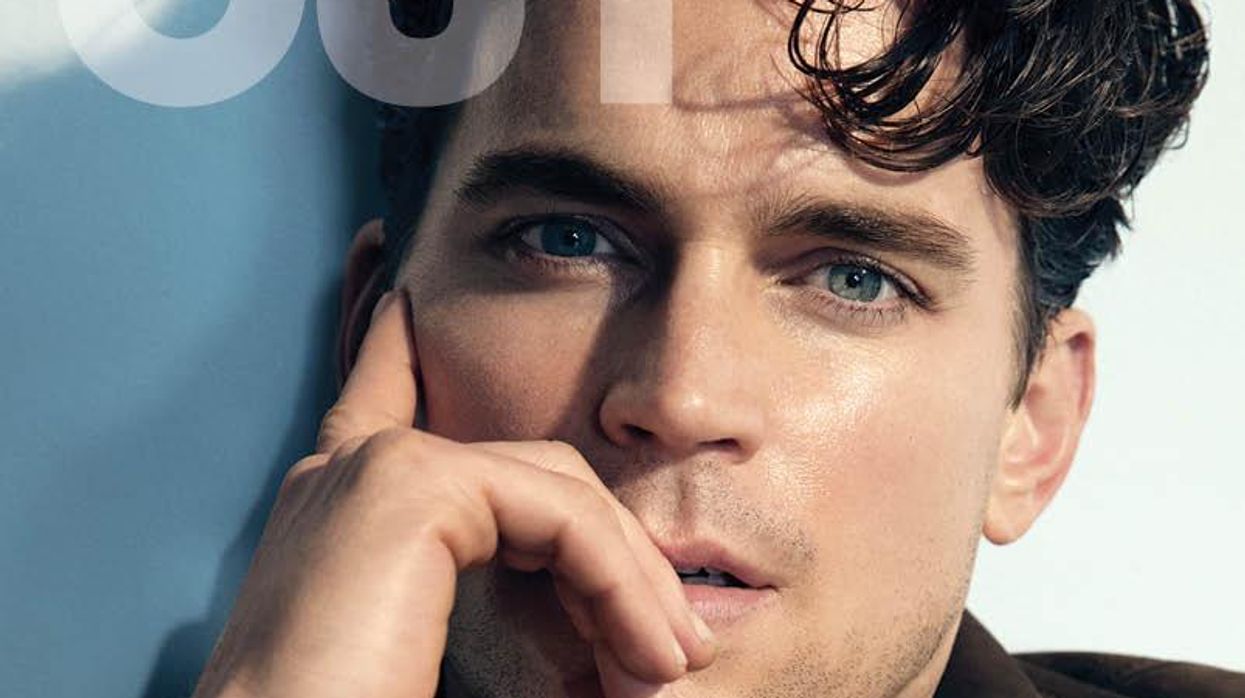

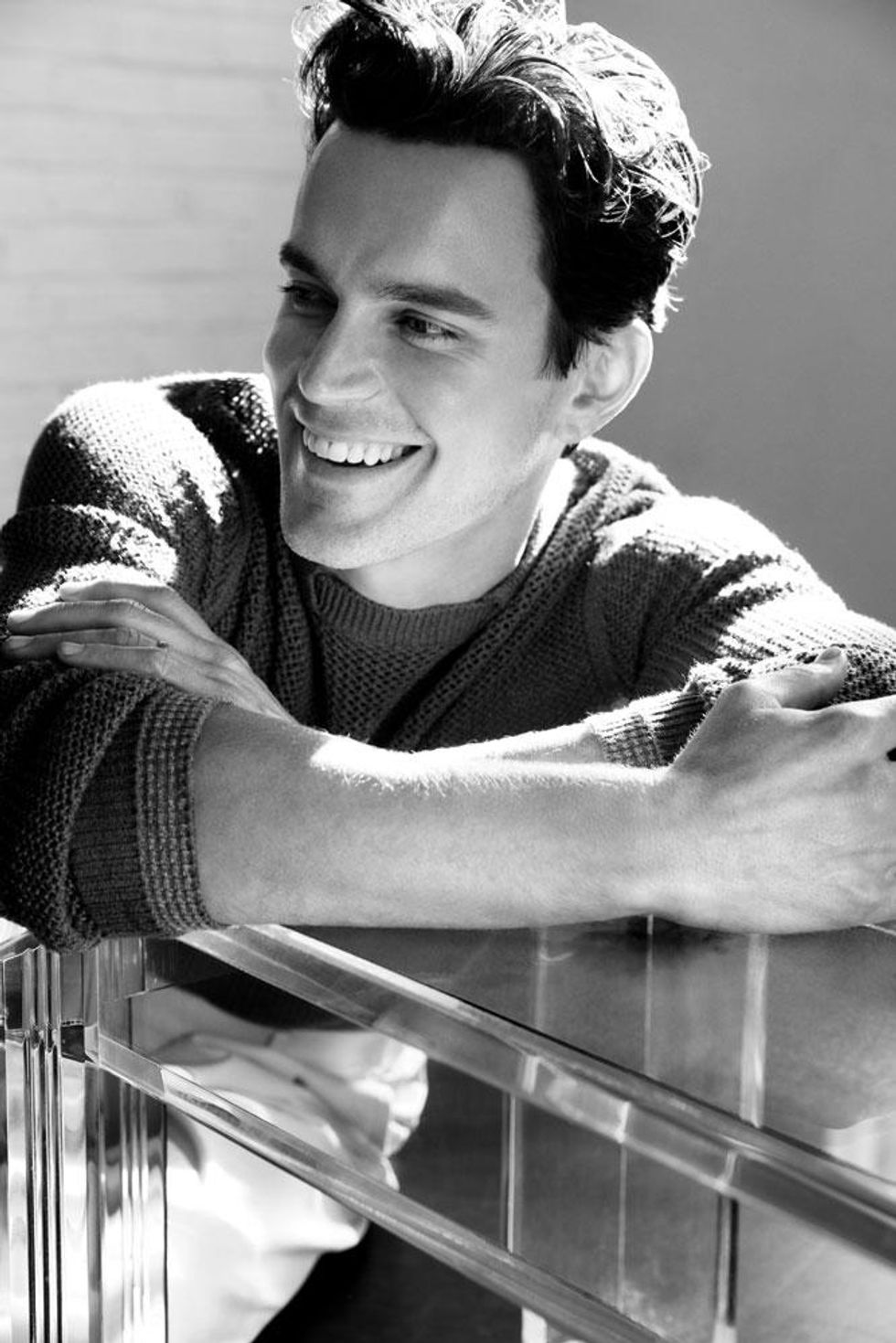

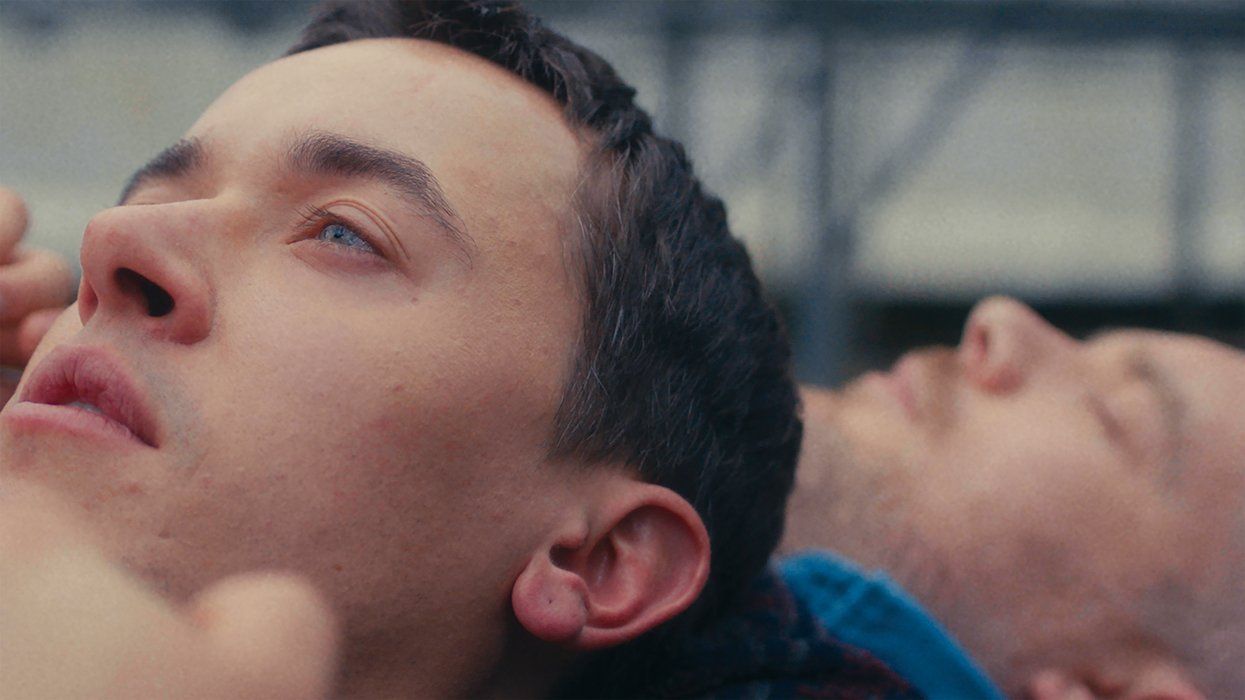

There's a nice symmetry in casting a gay actor from Texas to play a different kind of Hollywood outsider, as the producers of Amazon's The Last Tycoon have done with Matt Bomer, the former White Collar star who also won a Golden Globe in 2015 for his performance as Felix Turner in Ryan Murphy's HBO adaptation of Larry Kramer's The Normal Heart.

Related | Gallery: Hollywood Love Bomb, Matt Bomer

This time Bomer plays Monroe Stahr, a self-invented Jewish director in the mold of Irving Thalberg, one of early Tinseltown's great producers. Loosely based on F. Scott Fitzgerald's unfinished novel of the same name, The Last Tycoon is written and directed by Billy Ray, best known for his work as a screenwriter for crowd-pleasers such as The Hunger Games, though he also directed the critically acclaimed 2003 movie Shattered Glass, about the fraudulent and discredited journalist Stephen Glass. For his first long-form drama series, Ray has not skimped on period detail, and the production is achingly stylish and sumptuously lit. But it also promises to evolve over the course of its nine-episode season into a compelling creation myth of modern-day Hollywood.

Bomer, who started his career in theater, recently sat down with his old friend Andrew Rannells (Girls) to open up about Tycoon, the coming-out process, and his crazy stint as a soap star.

--

Matt Bomer: Let's get down to it -- brass tacks.

Andrew Rannells: I don't want to intimidate you, but I was a guest host once on the fourth hour of the Today show.

MB: Oh, with Hoda? Me too!

AR: That's so funny. But I cursed. Within the first 30 seconds I said "shit" on the air.

MB: How'd that go?

AR: We went to commercial and Hoda was like, "Hey, not a big deal, but you did curse."

MB: She low-key scolded you?

AR: Yeah, and I was like, "What?" I didn't even notice -- I was so nervous. But wait, we must have met in New York in 2004.

MB: It was through [Broadway actor]Gavin Creel.

AR: This will date the whole experience because I remember we had dinner at Cafeteria and then went to the Opaline.

MB: And now here we are.

AR: How long did White Collar [Bomer's USA series] run?

MB: Six years.

AR: So that's the same as Girls. It feels a little anticlimactic because I imagine your schedule was similar to ours -- we wrapped, then months went by, and then it aired, and you're like, I already grieved this, but now I'm going through it again.

MB: The whole experience of film or television -- time feels very fast, and very slow, and you're revisiting things. I still find live theater the most energizing. Every performance is unique, every audience is different, and there's an immediacy that's addictive, especially when you're in a great play like Book of Mormon or Falsettos.

AR: We performed Falsettos last fall a day after the election. It was rough to get through -- to show up on a Wednesday to do, like, three shows after that night.

MB: How was the audience?

AR: Angry. There were certain things that just landed in different ways. And that is the reason why it's so fun to do it, because it's a living thing -- it changes every time you step on stage. It's crazy.

MB: I just knew when I started doing theater in high school that these were my people, and then I went to theater school and I thought I was just going to be in theater for the rest of my life. And it was only by circumstance and luck and faith that I got to experience other mediums.

AR: Because then you were in Millie, right? That's when Guiding Light happened?

MB: When I got Millie, I had just moved to New York --

AR: That's Thoroughly Modern Millie, but in the theater we sometimes shorten the title. At least we didn't call it Thoroughly.

MB: We were waiting for the show to find a new theater when September 11 happened, and I lost my day job as a bellman at the Hudson Hotel in New York. It was like a ghost town for a while, so people in the service industry were getting laid off in order of seniority. I didn't know how I was going to pay my rent for the next four months while we waited for a different theater. I had an opportunity to audition for a soap opera, and somehow I got it, and it was really one of the best things that ever happened to me. It was the most insane circumstances on a daily basis. I told the writers, "Give me the craziest shit you've ever given anybody." And they obliged. I'll tell you what happened to my character in the course of a year and a half. I was a trust fund baby who bet my fraternity brothers that I could be the first to deflower the town virgin.

AR: There was a town virgin? Just one?

MB: The only virgin in town. She was kind of the grande dame's daughter, so a very precious character to those who followed the show. I'd get yelled at by airport staff: "Don't do Mara wrong!" Of course, I ended up falling in love with her.

AR: Sure.

MB: And then she found out about it -- and dumped me.

AR: Did you deflower her?

MB: No.

AR: Rats!

MB: We would always come very close and then someone would interrupt right at the moment.

AR: Were you ever naked on it?

MB: Oh, yeah. So I found a new girl, lost my trust fund, and I was scared she wouldn't love me anymore, so I did the only thing any logical, sensible person does when they lose their trust fund -- I turned to male prostitution. You only ever saw me with one client, who was like a really lovely, gorgeous woman in her 40s. And then she broke up with me, I went crazy, killed four or five people, abducted her to a remote cabin in the woods, and confessed that I had been molested by my female schoolteacher as a child, which was very topical at the time -- it was right before...

AR: Mary Kay Letourneau?

MB: Exactly. So I confessed to her and then committed suicide in front of her father and her new boyfriend by injecting myself with a syringe of insulin. And then, classically, hung on an extra day in the hospital to confess all my sins and apologize. But my favorite part of that entire experience was the writers coming up to me as I'm getting wheeled off the set in my hospital gown and saying, "Listen, if you ever want to come back, we've got it all figured out." And I always wanted to know, what was it going to be?

AR: There's still time.

MB: I loved the experience, and it was like a great graduate school. No one is giving you a lot of suggestions, so you have to learn how to make choices really quickly and trust your instincts.

AR: So let's talk about your new Amazon series, The Last Tycoon. Were you interested in Hollywood history before taking this on?

MB: Yeah. I had just reacquainted myself with The Day of the Locust, which is a great Nathanael West book and film. And I was just thinking about the scrappiness of that period and the people who came to this town to make something of themselves and to dream big. And then a couple weeks later [director] Billy Ray called and said, "Hey, I'm doing The Last Tycoon," and it was so serendipitous -- it felt like a dream, that it was all happening that easily. The next thing I knew, I was in a double-breasted suit on a set, speaking period dialogue.

AR: We sort of take that history for granted, but those people were creating a form, so there were no rules yet. It literally was the Wild West of show business.

MB: And what's interesting to me is how much has changed and how much really hasn't, particularly in Los Angeles. We've all been frustrated by this system, and the business aspect of things, but it is a necessary evil. At its best, it's friends making a business-savvy project, or putting a piece of art together.

AR: Did you know your co-star Kelsey Grammer before doing the show?

MB: Not at all. And I adored him. I think we all feel like we know Kelsey Grammer -- he's been in my living room since I first started watching television. But I didn't expect to love him as much as I love him. He's so open and loving and accessible.

AR: So how does it work on Amazon? They're going to release the whole series?

MB: All at once. We do a pilot, which people watched and rated, and that's how you get picked up for the other eight episodes.

AR: It seems like a much cleaner way than Nielsen [the ratings system used by networks].

MB: I'm grateful to be liberated from that.

AR: It must be nice not having to worry about advertisers. Did you keep track of that on White Collar?

MB: Initially I was really concerned because it was important that it do well. It was the first thing that had been marketed with me on the poster.

AR: It was all over New York.

MB: My airbrushed visage just staring down at you.

AR: Just getting graffitied. Dick drawn on.

MB: Exactly. That's when I knew I'd

made it.

AR: Isn't that satisfying?

MB: I would go down the subway and see a dick graffitied next to my face. I was like, "Yes!"

AR: Yay! And when is your new movie Walking Out released?

MB: They're thinking November or December.

AR: And you're playing the father of a teenage son?

MB: It's about a father and a son who are at odds and have been out of each other's lives. The son has been living with his mother in Houston and comes back to Montana, where the two of us reconnect on a hunting trip.

AR: How old is your oldest son?

MB: He'll be 12 in May.

AR: Was there a flash forward to being a father to a full-blown teenager?

MB: Josh Wiggins plays my son. His character is probably more extreme than our children will ever be, and I think my character is more extreme than I'll

ever be.

AR: That's what you say! If you start going hunting, I'll stop you.

MB: Well, I grew up hunting with my dad. I'm from Texas, and it was a rite of passage.

AR: What do you hunt in Texas?

MB: The one thing I would not kill was deer.

AR: So, like pheasant?

MB: I never killed a pheasant. I killed a duck, quail...we hunted geese. There's this tradition in the South where men bond with their sons in this unspoken way where you go out into nature and you sit together quietly with this independent activity that allows you to do so in a way that holds you accountable to each other. So a lot of the character is really a love letter to my dad. He actually came up to South by Southwest to see the film. My grandmother walked her first red carpet on her 87th birthday. My dad called me afterwards and said, "I saw some of myself up there on screen -- it was really odd, but beautiful." So it reconnected us in a great way. Where are you from?

AR: I was born in Omaha, Nebraska.

MB: You are so Midwest, I love it -- just a wide-eyed, bushy-tailed, handsome Midwesterner.

AR: Come on!

MB: But were you from an acting family?

AR: No.

MB: We had artists in our family, but they were like closet artists. My grandmother was a wonderful painter in her spare time, and my uncle was an incredible self-taught guitarist-singer-songwriter, but never an actor. So I was definitely the black sheep in that way, but I had a really specific plan -- we had this crazy high school where I was doing scenes from Larry Kramer plays and Angels in America when I was 14 years old.

AR: In Texas?

MB: In semi-rural Texas. I think some people blanched, but they respected the material. I never felt any condescension around it.

AR: I assume you get this a lot as well, but recently I have only been playing gay characters, and I get a lot of people asking, "Isn't that limiting?" Which I find to be the most condescending question, because it's a facet of your personality, of your humanity, but it doesn't mean that you automatically have to act one way. I think anybody who asks that question is really showing they have such a limited scope of who people are. The only time it's limiting is when the writing is bad. And there's a lot of bad writing out there.

MB: And they write it in a limiting fashion, so you can't break out of it.

AR: And I know you get this a lot: "Oh, I didn't know you were gay."

MB: One of the ways I learned how to act, really, is by having secrets, and having to function as a kid in a public school in suburban Bible Belt Texas. Subsequently I worked on a gas pipeline with my brother for a while -- there were ex-cons with us. It was not an environment where it was safe to be gay.

AR: With that face, you worked on a pipeline? Did you put on an eyepatch or something? A goatee?

MB: No, but I did learn how to protect myself -- it was literally acting of the highest stakes. I had my brother to protect me, but as terrible as it may sound, it was a way I learned to select behavior and make choices, even if it was a ruse just to survive, you know?

AR: Which, sadly, a lot of gay men have to do.

MB: Not so much now, I feel.

AR: Well, in different parts of the country though. Even in New York, where I surround myself with like-minded people, I remember walking one night in Times Square and someone spitting in my face and calling me a f****t. That's actually the reality for a lot of people all the time, and it's not just a smack in the face -- it's a thing they're constantly navigating.

MB: I remember when I traveled to Ireland to work abroad when I was in college. I was sitting outside Shannon Airport in Ireland, and I decided I was going to cross my legs and write in my journal. And a car of Irish ruffians came by -- and this is not reflective of the Irish people, because they are wonderful, loving, embracing people -- but they were like, "Fucking poofter." And I thought, OK, I'm going to uncross my legs and not cross them again while I'm here.

AR: I'm always amazed, particularly on Broadway, when you come across an actor who's struggling with coming out. Like, this is the safest place possible for you to be right now. It really does just show that no matter how many laws are passed, or how many TV shows portray gay couples, it really is such an internal conflict for people. Did you struggle with that with your family?

MB: Oh yeah! I was raised in a conservative Christian household. We weren't even allowed to watch "secular" television, anything that was deemed not proper for Christians.

AR: Full House? Did you watch that?

MB: I remember watching reruns of the short-lived Nell Carter sitcom Gimme a Break!

AR: First of all, that was not short-lived.

MB: It was not?

AR: Matt Bomer, that was a fucking hit show!

MB: I want to say that since then, my family's come around and they are amazing, incredible grandparents to our kids.

AR: But even if your family is great, there's still going to be a struggle within yourself to sort of figure out, Am I comfortable with this? I have a lot of friends who fretted quite a bit over their family's reaction, but it was more the buildup of telling them that was sort of crushing them in a way.

MB: Telling your family is a huge, huge deal. I really view my life as divided between the time before I told my parents, and the time after. And the decisions I made, and the life I lived, before and after, are vastly different. It's night and day.

AR: When did you come out to yourself versus when you came out to them?

MB: I was at the Utah Shakespeare Festival, and I was doing Romeo and Juliet and Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat in rep, and I remember someone there who was a hair and makeup artist who I found really inspiring. I thought, If this person can live their truth, what am I doing? I was actually in the middle of doing sit-ups, because I needed some kind of physical release. And I was dating a girl in the company at the time.

AR: Who did she play? Potiphar's wife?

MB: When I say dating, I mean we went to a couple of movies together.

AR: You made out a little bit.

MB: I thought she was really cool and talented, frankly. I just wanted to hang out with her. And then I just thought it was time to live my life truthfully. How about you?

AR: I don't know how I hit the jackpot in Nebraska, but I had two friends from kindergarten to eighth grade who are now gay, and we would literally lip-synch to Cher in the basement, and then to Kylie Minogue's "I Should Be So Lucky." And I had three sisters and a brother, and it was no big surprise that Andy was gay. It was a very easy transition. But I didn't say the words until right before I left for college, on the off-chance that something was going to go awry. If somebody had a problem, I wanted to have an exit strategy. So I waited until after I graduated high school, and was like, "I'm gay, I gotta go."

MB: I wrote a letter to my parents. I would have lost my sense of direction if I tried to do it in person.

AR: How did they respond?

MB: There was radio silence for a long, long time, at least six months.

AR: Oh, Jesus. That is a long time.

MB: And then I came home and we had the blowup that I'd always feared. But we got that out of the way, and we got down to the business of figuring out how to love each other. I would say within a matter of years we started to figure it out. It was a struggle. It's a struggle for anybody to take their paradigms and set of beliefs and understandings and completely flip the script. So I'm empathetic toward everyone. And my family is so loving. My mom just asked me, [my husband] Simon, and the boys to go down and speak to her women's group in Houston so, you know, I'm here to tell people it can get better. Because I had so many people in my life saying, "You need to get rid of all expectations -- you need to cut them out." But I was like, "They're my family."

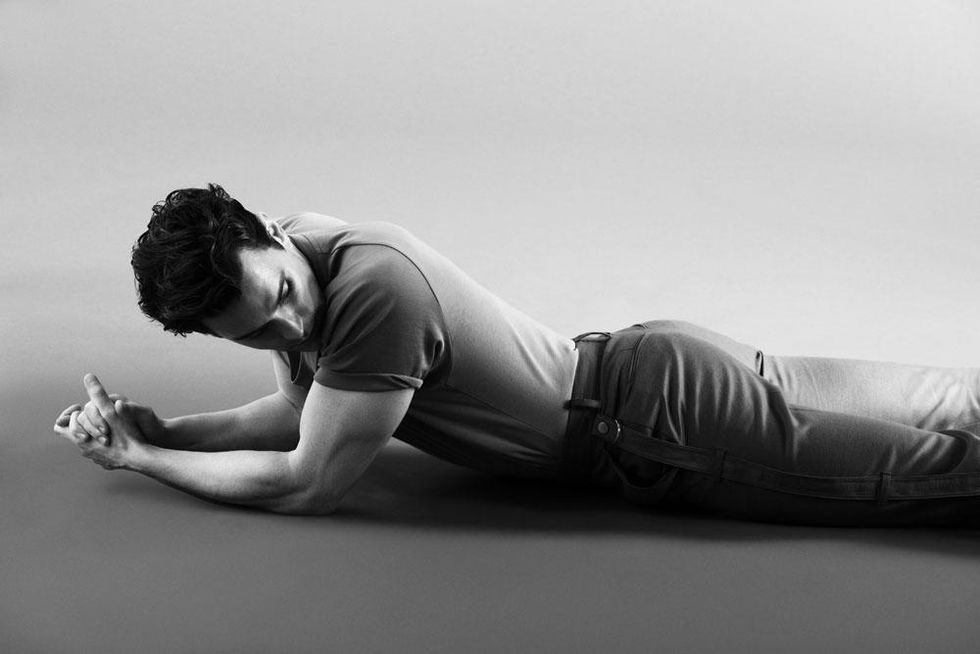

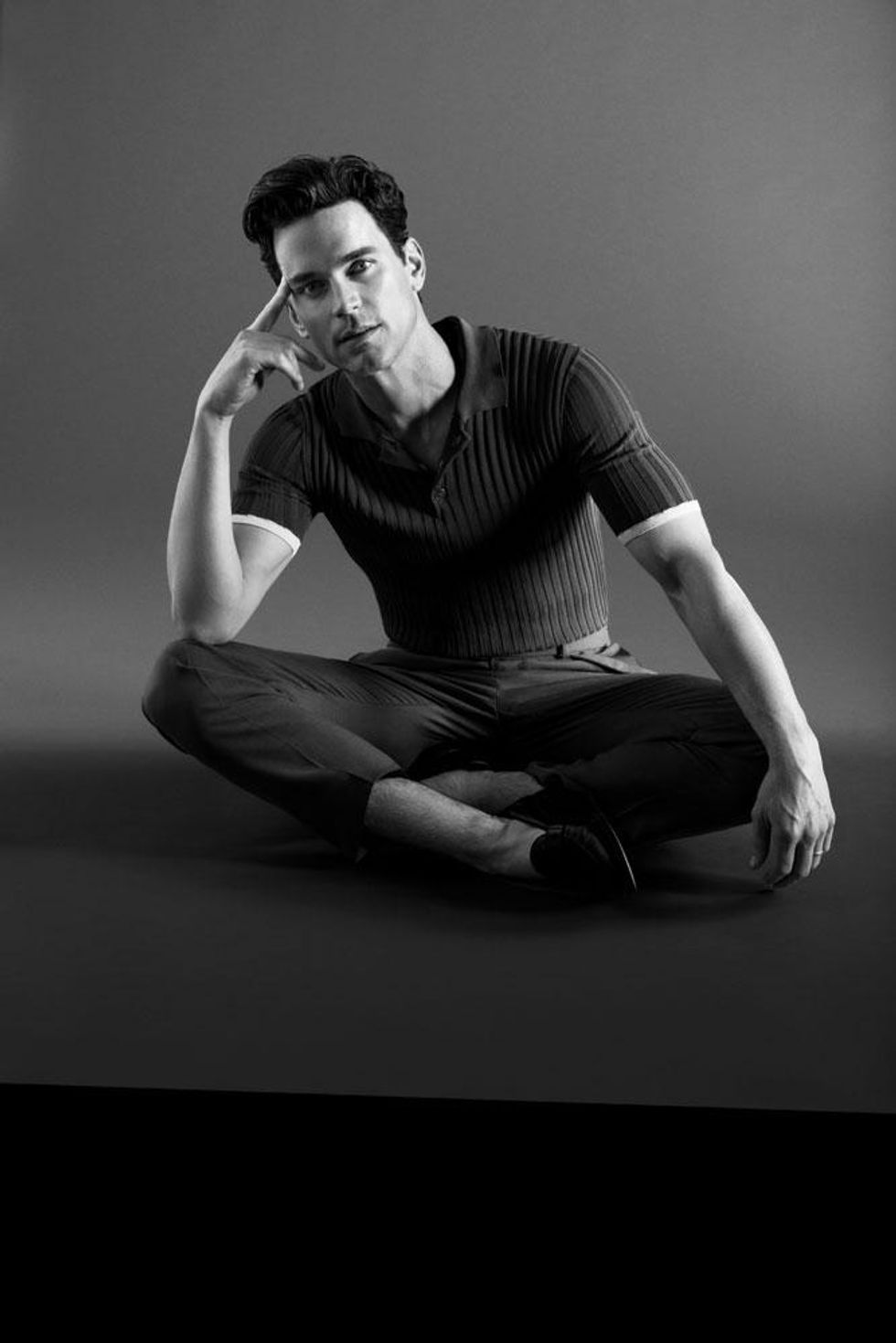

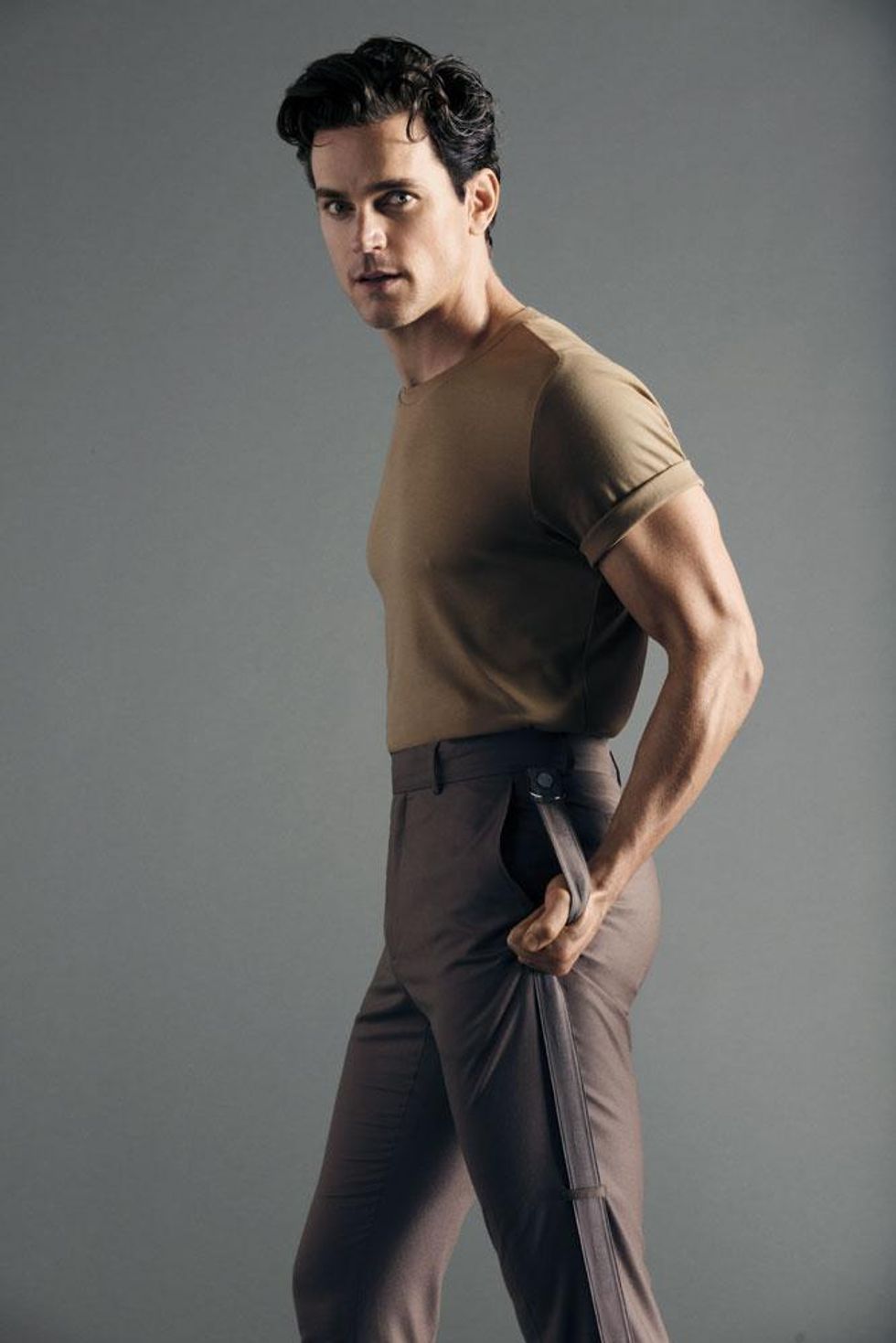

Photography: Doug Inglish

Styling: Grant Woolhead

Market Editor: Michael Cook

Fashion Assistant: Luke Prusinski

Groomer: Diana Schmidt (Something Artists)

Shirt & Pants: Valentino, Shoes: Tom Ford

Like what you see here? Subscribe and be the first to receive the latest issue of Out. Subscribe to print here and receive a complimentary digital subscription.